Competition is a powerful influence in determining the extent and nature of a firm’s marketing activities. Very few firms operate in a market environment all by themselves. Most companies face competition from at least one other business, and usually from several. Broadly speaking, all firms compete with each other for the buying power of consumers.

However, from a more practical viewpoint, a business generally views as competition those firms that market products similar to, or substitutes for, its product in the same market(s).

Thus, competitive forces make substitutes available for almost every product or service on the market. They may not be perfect substitutes. Yet under certain conditions, bicycles are substitutes for cars. Most firms cannot believe that “we have no competitors” because consumers make trade-offs.

When the costs of automobiles and gasoline become too high, people may switch to bicycles.

To compete with other companies operating in the marketplace effectively, the marketing executive needs to know who the competitors are, what they are doing, and have a strategy for counteracting their activities.

The products a firm offers, their prices, how they are promoted, and the channels of distribution used all depend to some extent on what the competitor is offering.

Furthermore, the marketing executive must assess possible competition from industries other than its own and foreign industries.

Effective marketing programs can be developed by adjusting to forces within the existing market and monitoring potential competition from the outside. A marketing organization, therefore, must deal with competitors in two ways.

First, the company must find out who its competitors are and what they are doing.

Second, it must decide how to act or react in light of competitors’ activities.

It is relatively easy for a company to identify its apparent competitors, but it is difficult to identify the range of actual and potential competitors. “A company is more likely to be outdone by its emerging competitors or new technologies than by its current competitors.” A company may face four levels of competition. These four levels are based on the degree of substitutability of the product.

Let us now have some idea on these four levels of competition:

- Brand Competition: If other companies offer similar products and related services at similar prices to the same customers, we can say that the company is facing brand competition.

- Industry Competition: If all companies in the same industry make the same product or class of products, they consider it industry competition. Aromatic, for example, will see here all cosmetics companies as its competitors.

- Form Competition: Form competition occurs when a company sees its competitors as manufacturing products that supply the same service. For example, an automobile manufacturer would compete against other automobile manufacturers and manufacturers of other vehicles like buses, trucks, cycles, and motorcycles.

- Generic Competition: If a company considers all other companies as its competitors who compete for the same consumer discretionary income, we call that a generic competition.

A company’s competitors can also be identified from two other perspectives, and they are more specific. They are industry competition and market competition.

Industry Concept of Competition

The law defines industry as any business, trade, manufacture, culling, service, employment, or occupation. The industry here includes all concerns involved in a particular trade or business. The jute industry, for example, includes all firms in the jute business.

Philip Kotler defines industry more precisely. To him, “industry is a group of firms that offer a product or class of products that are the close substitutes of each other.”

If a buyer can use a product instead of the other satisfying the same type of need, the two products can be called substitutes. Tea and coffee in this respect can be called substitute products. There are several ways to classify an industry.

The usual ways are the number of sellers and degree of differentiation, entry and mobility barriers, exit and shrinkage barriers, cost structure, vertical integration, and degree of globalization.

Detail discussion on the above is not possible in this text since this is not an economics text. Let us now look at them:

- Number of Sellers and Degree of Differentiation

- Entry and Mobility Barriers

- Exit and Shrinkage Barriers

- Cost Structure

- Degree of Vertical Integration

- Degree of Globalization

1. Number of Sellers and Degree of Differentiation

The number of firms that control the supply of a product, and the homogeneity and heterogeneity among the products may affect the strength of competition.

When only one or a few firms with more or less homogenous offer control of the product, competitive factors will exert a different influence on marketing activities than when there are many competitors.

The table below shows four general categories or models of industry structure:

General Industry Structures and Their Characteristics

| ||||||

| Type of Structure | Number of sellers | Ease of entry | Product | Knowledge of Market | Price | Marketing effort |

| Monopoly | One | Many

Barriers | Almost no substitutes | Perfect | Much control over price | Little |

| Oligopoly | Few | Some barriers | Homogeneous ous or differentiated | Imperfect | Pricing in concert | A very large amount of nonprice competition |

| Mono polistic competition | Many | Few

Barriers | Product differentiation with many substitutes | More knowledge than oligopoly | Pricing in concert | The very large amount of non-price competition |

| Perfect competition | Unlimited | No barriers | Homogeneous ous products | Perfect | No control over price | None |

Monopoly Structure

A monopoly or monopolistic market structure is that structure where only one large firm operates in the marketplace and has complete control. By definition, no competitors exist, and no competitive forces are at work. Utility companies (electricity, gas, water, etc.) could be examples of monopolies.

In a monopolistic situation, a firm’s product has no close substitute. In this case, a single seller can erect barriers to potential competitors. The firm has much control over the price but can sell only what the market will take at its price.

The entry of other firms is very difficult because resource access is blocked. Marketing efforts are found little here, but the monopolist can enjoy benefits if less product elasticity is created.

Oligopolistic Structure

The oligopolistic market structure is one of the most important structures because of the sheer market power it contains. This structure is characterized by a relatively small number of competitors who are very large in size.

Because there are so few, each knows what the others are doing. They also have at least some capacity to replicate each others’ marketing strategies. This type of structure assumes that consumers do not always behave rationally, nor do they have the perfect market knowledge found in a purely competitive market.

Examples of this type of market structure are numerous: automobiles, steel, oil, chemicals, rubber, etc. Theoretically, every oligopolistic firm has a great capacity to influence the market environment simply because of its size. Yet, sometimes this very capability creates something of a stand-off.

The firms are somewhat reluctant to cause too many disruptions since the competitors will react very quickly. In practice, most competitive forces occur in the area of promotion.

At least in the short run, unique promotion methods coupled with creative advertising, personal selling, or sales promotion messages can have a significant impact. Pricing in concert is a strong tendency found in an oligopolistic structure.

Monopolistic Competition

When marketing executives distinguish their products from those of the competition, even though they are essentially alike, a monopolistically competitive structure is created.

In these markets, there are a fairly large number of competitors selling relatively homogeneous products. The differences between this structure and a purely competitive market structure are that the firms are bigger, and the consumers do not have full market knowledge, nor do they always behave in a highly rational manner.

The marketing executive attempts to create a perceived difference about a product and hopes that the consumers develop a preference for it over the competing merchandise.

The uniqueness may be in the form of better quality, better value for the money, convenience of purchase or service, or some other factor. Even though all of the products are functionally similar, people may believe they are different.

When this occurs, competitors’ products are no longer substitutes, and the firm can engage in its own effective marketing strategies. It seeks a differential advantage to obtain a partial monopoly in its market.

Perfect Competition or Purely Competitive Structure

Economist Adam Smith envisions this type of structure. Over time, however, this vision has proven to be more idealistic than realistic.

The concept of pure competition holds that a large number of small companies compete in the marketplace, the products they sell are perfect substitutes, all consumers have the perfect market knowledge and are rational buyers, and no barriers exist to firms wanting to enter the market (or to those wanting to leave it).

Under this structure, a marketing executive’s job is relatively simple. Since all the products are the same, and all consumers know it, there are really very few marketing executives to do.

If they raise prices, they will be driven out by new competitors, and there is no advantage to lowering prices since they assume that they will sell all they produce at the market price.

Furthermore, it makes little sense to promote or uniquely distribute the product since the firms are small, and consumers already know about the products.

This particular structure, as tranquil as it may sound, is largely a thing of the past. Although some agricultural products and industrial supplies in the West have market structures that approximate a purely competitive environment, they cannot fully satisfy its assumptions.

You should appreciate that the industry structure does not remain the same throughout. Rather it may change with the elapse of time. Many industries started as a monopoly and turned into oligopoly and finally took the shape of monopolistic competition.

2. Entry and Mobility Barriers

In some industries, it is relatively easier for other firms to enter. But, in other industries, it is quite difficult for a new firm to enter. It means that some industries are subject to entry barriers.

The usual barriers are high capital requirements, economies of scale, patents and licensing requirements, scarce locations, raw materials or distributors, and reputational requirements.

Some are intrinsic in nature among the barriers, while others are created deliberately by the existing firms. The barriers may be created either by a single firm or by the concerted efforts of all the firms operating in the said industry.

In addition to entry barriers, an existing firm may face mobility barriers that move into other segments it considers attractive. The mobility barriers may be created by a single firm or by the existing firms’ combined efforts in the said market(s).

3. Exit and Shrinkage Barriers

A firm has the right to leave the industry if it finds the industry unprofitable or unattractive from any other point. But, a firm always cannot has such an option. That is, it may even face exit barriers.

The exit barriers that a firm may face are legal or moral obligations to customers, creditors, and employees; government restrictions; low asset salvage value due to overspecialization or obsolescence; lack of alternative opportunities; high vertical integration; emotional barriers, and so on.

In this circumstance, a firm may decide to stay in the industry to cover its variable costs and a part of fixed costs by selling its produce.

If quite a few firms pursue such a policy, it dampens profits for everyone, and what the other firms do in such a situation is to help those wanting to exit. It may be done by buying their assets, meeting customers’ and creditors’ obligations.

Some of the firms in a particular industry may suffer a loss due to their inefficient sizes and may wish to downsize.

But it may also be difficult due to the barriers faced, such as contract commitments and stubborn management. Here again, competing firms may help firms not optimum in size to downsize their operations.

4. Cost Structure

Cost structure may vary from industry to industry.

By cost structure, we mean here the mix of costs. Some industries may involve heavy marketing and distribution costs, while others may involve heavy research and development costs, and another may involve heavy production costs.

Every firm in a particular industry should try to minimize its major costs by making it optimum. A strategic move may help a firm to minimize its major cost and thus operate economically and profitably.

5. Degree of Vertical Integration

In vertical integration, “operations in successive stages of production or marketing or both are carried on under single ownership.” Vertical integration may take two forms, such as integrating forward and integrating backward.

A garment manufacturer, for example, may go for vertical integration. It may set up or buy yarn manufacturing factories (backward integration) and own transport facilities(forward integration) to ship its output.

It may help a company reduce costs, wield more control, and achieve economies of operation. The cost reduction helps integrated firms or operations lower sales prices and have more market coverage and profits.

Yet, it runs the risks of cost increase because of lesser flexibility and improper handling of certain operations.

6. Degree of Globalization

Some industries operate locally and sell their outputs/services locally. Again, there are industries whose products/services are sold beyond the places of production or origin.

Industries that operate globally must be very smart in terms of their operations and offers. To be attractive and compete worldwide, they must control costs and adopt the latest technologies to prove their worth and penetrate the global market.

Market Concept of Competition

While discussing the industry concept of competition, we considered companies making the same product for a market. There we have overlooked the needs of customers. Companies basically produce their products/services to satisfy some or other needs of customers.

Therefore, we can look at competition from the viewpoint of customer need satisfaction, that is, considering companies trying to satisfy some customer need through their offers. This is more a logical approach to view competition. A trucker, for example, normally sees its competition as other truckers.

From a customer point of view, a customer hiring a trucker is actually buying a transport service for which he may also go to the railways, steamer companies, or any other transport operator.

If a company looks at its competition from this perspective, it will visualize potential competition. This visualization will help a company strategize its operation to make it more competitive in the face of an everchanging environment.

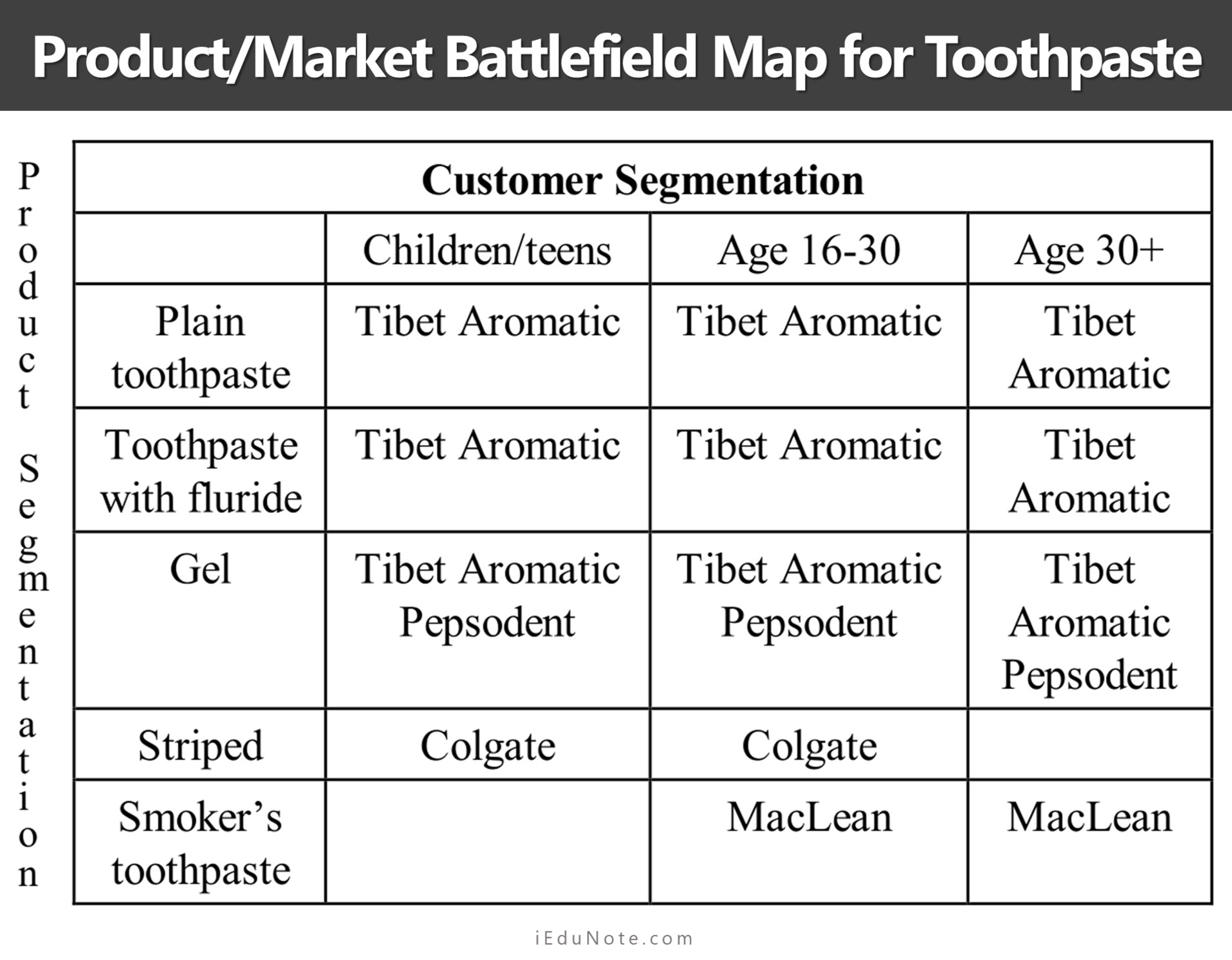

From the market concept of competition view, a company can identify its competitors by linking industry analysis with market analysis. By mapping out the product/market battlefield, a company can comfortably identify its present or potential competition.

A hypothetical product/market battlefield map for toothpaste can be seen below :

In the above figure, the product/market battlefield map for toothpaste is illustrated according to the customer age group and product types.

It is seen in the figure that nine segments of the toothpaste market are occupied by two brands viz. Tibet and Aromatic, where, Pepsodent occupies three, and Colgate and McLean both occupy two segments.

A particular brand not occupying a particular segment may also be aimed at that segment. The firm deciding to offer its brand in the untapped segment must estimate its market size, shares of the existing competitors, capabilities, entry barriers, competitors’ objectives, and strategies.

After the above estimates, a firm can decide to offer its brand to new segments if it finds it attractive.