Attitude is considered to be the most important determinant of buying behavior. Marketers, therefore, pay close attention to consumers’ attitudes. A marketer needs to know the important aspects of consumer attitude. Equally important for a marketer is to understand how attitude is organized.

Cracking Consumer Attitudes: Key to Marketing Triumph

Background of the Attitude Study and Consumer Behavior

Consumers’ motives determine or activate behavior resulting in purchases and consumer behavior cannot be predicted simply from motivations. Other intervening individual factors come into play.

These factors tend to influence the consumer’s perception of various products and brands of products that may be utilized to satisfy his/her needs.

Some of the important individual intervening variables are consumers’ attitudes, self-image, and habits. You know that the purchase decision process starts with the identification of a need that is unmet.

Once the desire for a need satisfaction arises, the next step that the consumer passes in the purchase decision-making process is evaluating different products or services as ways of satisfying the unmet need.

Evaluation helps the consumer decide the brand to be purchased or the seller to satisfy his need.

His attitudes play an important role in the process of evaluating alternatives and selecting a particular brand of product so that the consumer can satisfy his need. Attitudes thus play a direct and influential role in consumer behavior.

By this time, it should be clear to you that consumers’ attitudes toward a company’s products significantly influence the success or failure of its marketing strategy.

Attitude study is important for marketers because it affects consumers’ selective processes, learning, and ultimately buying decision-making.

As consumers’ attitudes influence their intention to buy, knowledge of different aspects of consumer attitudes may help marketers make a sales forecast for their products.

Measuring consumer attitudes may help a marketing executive better understand both present and potential markets.

As attitudes often affect the consumer’s decision-making process, marketers must understand attitude formation and change if they expect direct marketing activities to influence consumers.

Awareness of consumer attitudes is such a central concern of both product and service marketers that it is difficult to imagine any consumer research project that does not include the measurement of some aspect of consumer attitudes.

An outgrowth of this widespread interest in consumer attitudes is a consistent stream of attitude research reported in the consumer behavior literature.

It is well understood that attitude has been one of the most important topics of study in the consumer behavior field.

Attitude study may contribute to decisions regarding new product development, repositioning existing products, creating advertising campaigns, and understanding the general pattern of consumer purchase behavior.

Thus, understanding what an attitude is, how it is organized, what functions it performs, how it can be measured, and how a marketer can change an existing attitude is very important for a marketer to combat competition successfully.

The following few important and generally accepted findings on consumer attitudes further justify the importance of attitude study for a marketer taken from the studies of Alvin Achenbaum; Henry Assael, George S. Day; Frederick W. Winter; and Steward W. Bither, Ira J. Dolich, and Elaine B. Nell.

- Finding #1: Product usage tends to increase as consumers’ attitudes toward a product become more favorable. Usage tends to decline as attitudes grow less favorable.

- Finding #2: The reason for different market shares occupied by different sellers in a product category is the differences in consumers’ attitudes toward different brands.

- Finding #3: Marketers may try to change consumers’ attitudes toward their products, aiming to increase sales through persuasive communications. But, they should bear in mind that many other variables determine the effectiveness of such communications.

- Finding #4: Consumers may likely change their attitudes toward the existing products if exposed to new ones. It is, therefore, important for marketers to even reinforce existing positive attitudes.

Attitude Defined from Consumer Behavior Point of View

Everyone adopts conscious and unconscious attitudes toward ideas, people, and things they are aware of. Allport defined an attitude as a mental state of readiness, organized through experience, exerting a directive influence upon the individual’s response to all objects and situations related to it.

It extends to beliefs and knowledge of products as well as to people and events. It also covers feelings, such as likes and dislikes created, and a disposition to act or act because of such feelings and beliefs.

You should keep in mind that there is nothing necessarily right, wrong, or rational about attitudes. You should also note that consumers do not have to have direct experience with products and services to form an attitude toward the product or service in question.

Berkman and Gilson, citing Daryl J. Bem, described attitudes as our likes and dislikes, affinities for and aversions to situations, objects, persons, groups, or any other identifiable aspects surrounding us, including abstract ideas and social policies.

Attitude, like so many concepts in the behavioral sciences, though it is a word used in everyday life and conversation, has a more precise meaning within the context of psychology.

It refers to the positive or negative feelings directed at some object, issue, or behavior. It is a learned predisposition to respond in a consistently favorable or unfavorable way to a given object.

Attitude can also be defined as a predisposition toward some aspect of the positive or negative world. You should note that this predisposition can’t be neutral. That is, a neutral attitude is virtually no attitude.

Marketers and psychologists know that consumers’ attitudes are mixtures of beliefs, feelings, and tendencies to behave in particular ways. That is the reason why marketers try to establish favorable beliefs about their offers.

The beliefs, feelings, and tendencies lead to favorable responses resulting in a purchase. An individual’s attitudes constitute his mental set that affects how he will view something, such as a window providing a framework for our view into or out of a house.

In the words of John W. Newstrom and Keith Davis, “The window allows us to see some things, but the size and shape of the frame prevent us from observing other elements. Besides, the color of the glass may affect the accuracy of our perception, just as the ‘color’ of our attitudes has an impact on how we view and judge our surroundings.”

Thus, it is an individual’s point of view toward something, which may be a product, an advertisement, a salesperson, a company, an idea, a place, or anything else.

To understand attitude, check out our post on definitions of attitude and determine the important aspects of attitude from this definition and those given above.

Important Aspects of an Attitude

Analyzing the above definitions and the discussion made above, we can identify the following few aspects of an attitude:

Attitudes are Learned

Individuals do not bear with attitudes. That is, attitude is not programmed genetically.

Individuals rather learn attitudes through information received from the environment. An individual may receive information both from his commercial and social environments.

Second, they learn attitudes through direct experience with the attitude object.

For example, one may buy and use a particular toothpaste brand and can develop a positive or negative feeling toward the brand.

Third, attitudes may be learned through a combination of information received and experience with the attitude object.

For example, one may read an advertisement (information) and buy and use the product.

As attitudes are learned, marketers may provide information to customers through marketing communication tools and distribute free samples for customers to have experience with the product, thus helping them form attitudes toward the product.

Attitudes are Predispositions to Respond

Attitudes imply a covert or hidden behavior, not overt or exposed. That is, others cannot observe them (attitudes).

One cannot see others’ attitudes or verify them; attitudes can be felt. They are the individuals’ predispositions to evaluate some symbol or object or aspect of his world favorably or unfavorably.

Attitudes may be expressed verbally through opinions or non verbally through behavior. It means that attitudes are hypothetical make-ups or constructs. These hypothetical constructs lead to actual overt behavior.

For example, if an individual is favorably predisposed toward a brand, he is likely to recommend others to buy that brand, or he may purchase the brand himself.

Attitudes are Consistently Favorable or Unfavorable Responses

Attitude toward an object leads to responses toward that object.

If an individual’s attitude is found favorable toward an object, he is likely to make positive responses toward it, and this tendency is likely to be fairly consistent.

In the case of a negative attitude, negative responses are likely to happen and happen consistently again.

Attitude Objects

It was mentioned earlier that attitudes are directed toward some object. In this case, the object may include a product, company, person, place, service, idea, store, issues, behavior, and so on.

Attitudes Have Degree and Intensity

Attitudes can be measured or quantified. That is, they have degrees.

For example, one may develop a highly positive attitude toward a particular brand, and another may develop a moderately positive attitude toward the same brand.

By this, you understand that attitudes have degrees.

Moreover, they have intensity, that is, the level of certainty or confidence of expression about the attitude object. For example, one individual may be highly confident about his belief or feeling, whereas another individual may not be equally sure of his feeling or belief.

Models Explaining How Attitudes are Organized or Formed

Understanding the structure of attitude is important because it helps us know how attitude works. There are quite a few schools of thought on attitude organization.

Each of these thoughts represents a model of attitudes. Out of these few orientations, two are noteworthy. They are;

- The tripartite view or three-component attitude model;

- The multiattribute model developed by Martin A. Fishbein.

Though these two models are considered as competing viewpoints, they are not actually inconsistent with one another.

Three-Component Attitude Model

- Cognitive Component (awareness, comprehension, knowledge),

- Affective Component (evaluation, liking, preference), and

- Action Tendency or Conative Component (intention, trial, or purchase).

Cognitive Component

Cognition refers to all beliefs that an individual holds for the attitude object. Let us say we are talking about an individual’s attitude toward a particular brand of toothpaste. His cognitive component of

attitude toward the said brand, say, ‘Pepsodent,’ may be expressed as, “Pepsodent whitens teeth.” How does he say that this particular brand of toothpaste whitens teeth? This is based on his cognition or knowledge about the brand. His cognition may be developed through reading, listening to others, or through the experience.

This aspect of attitude tells us how he evaluates the attitude object. The evaluation is usually based on his knowledge about different aspects of the attitude object and his beliefs on these aspects.

His evaluation based on the knowledge or cognition tells him whether to see the attitude aspect favorably or unfavorably and the action he should take in case of an unfavorable attitude developed toward the object.

For example, if an individual holds a negative attitude toward cigarette advertisements, he may not buy magazines, putting on cigarette advertisements, or even destroy the magazines publishing cigarette advertisements.

Affective Component

Feeling or affect component of an attitude relates to positive or negative emotional reactions to the attitude object. For example, if an individual believes that ‘Pepsodent’ toothpaste whitens teeth (cognition), the affective component of his attitude toward ‘Pepsodent’ may be expressed as: “I like Pepsodent.”

Action Tendency or Conative Component

The third component of an attitude, the conation or action tendency component, encompasses intended and actual or overt behavior to the attitude object. So, this is a predisposition to behave in a particular way toward the attitude object.

For example, if an individual’s attitude toward ‘Pepsodent’ is positive, he may be intending to buy or actually buy ‘Pepsodent’ toothpaste. This component of his attitude toward ‘Pepsodent’ may be expressed as: “I like to buy Pepsodent” or “I regularly use Pepsodent.”

The three-component model of attitude advocates believes that these three components are an integral part of an attitude. That is, they work together. In other words, in every attitude, these three components work together; maybe their degrees vary. It is also argued that there are consistencies among the components. If one connotes positive meaning, the other two will also connote the same.

For example, suppose an individual believes that a particular brand is good (cognition). In that case, he is likely to favor that brand (feeling or affect) and will buy the same once he requires the product (action or overt behavior). The problem with this model is that many empirical investigations do not yet substantiate it.

Moreover, it isn’t easy to measure each of these components of a given attitude. As a result, this model has minimal real-life use in measuring consumers’ attitudes.

Multi-attribute Model of Attitude

Quite a few models of attitude show the connection between perception and preference or attributes and attitudes.

These models are often referred to as evaluative belief models of cognitive structure to emphasize that attitudes are the product of evaluations of the attributes and beliefs about how much of attributes are possessed by the attitude object. One such model has been developed by Martin A. Fishbein, which is widely used.

According to this model, attitudes are viewed as having two basic components. One is the beliefs about an object’s specific attributes (product, here in consumer behavior). The attributes could be the product’s price, quality, size, shape, design, distinctiveness, durability, availability, packaging, and so on.

The other component is the evaluative aspects of consumer’s beliefs on different aspects of the attitude object. It implies how an individual evaluates the importance of each attribute of the object (product) in satisfying his/her need.

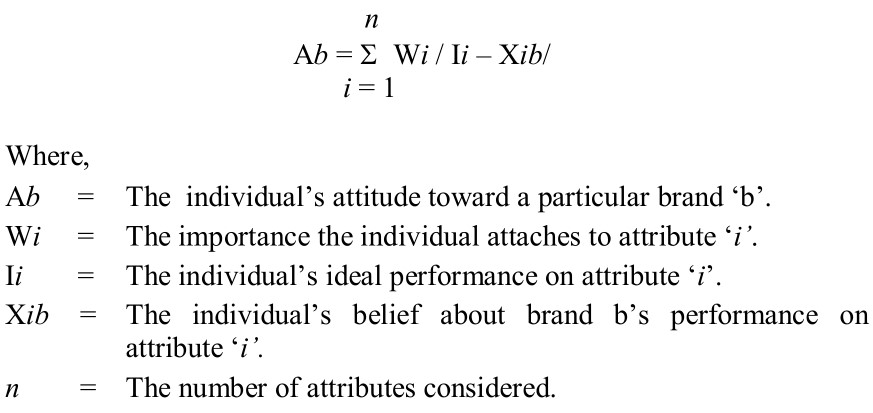

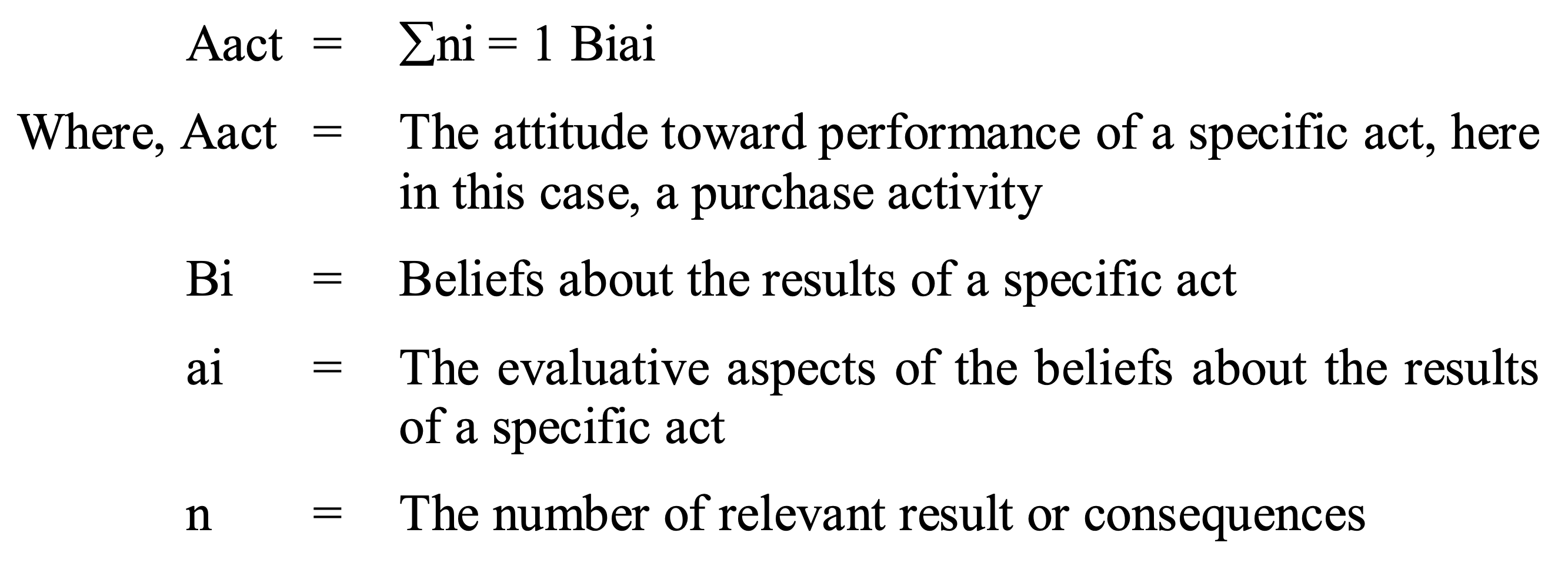

Fishbein’s model may be formulated as below:

The attitude of the individual toward a particular brand is thus based on how much the brand’s performance on each attribute differs from the individual’s ideal performance on that attribute, weighted by the importance of that attribute to the individual. Let us try to make you understand this model through an example.

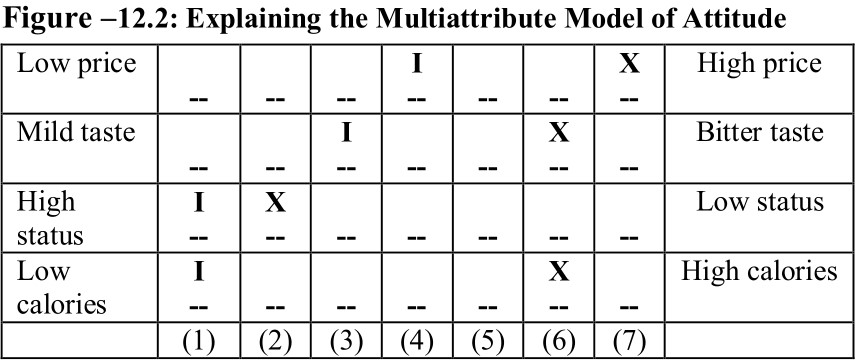

Let us assume that a segment of cola drinkers perceive the “Y” brand of cola to have the following levels of performance on four attributes such as price, taste, status, and calories (see the figure given below) :

From the above figure, it is seen that this segment of consumers believes (i.e., the X’s) that brand “Y’ of cola drink is extremely high priced, very bitter in taste, very high in status, and very high in calories.

The above figure shows that consumers’ ideal brand of cola drink (i.e., the I’s) should be medium-priced, slightly mild in taste, extremely high in status, and extremely low in calories.

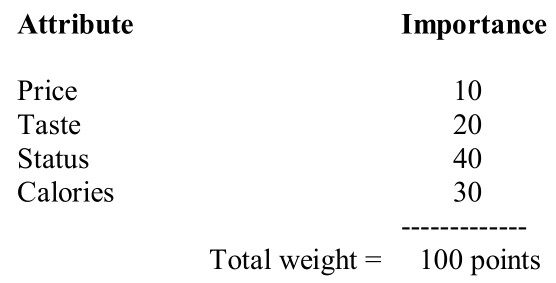

It is assumed that these attributes are not equally important to consumers. We can assign hypothetical weights to these attributes as follows based on their relative importance to consumers:

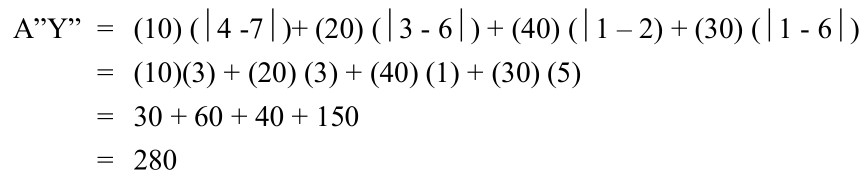

From the above distribution of weights on each of the four attributes consumers consider in the case of buying cola drink and the figure on the previous page, we can measure the attitudes of a segment of consumers toward the cola brand “Y” as follows:

Here we can find that the computed attitude index toward the cola brand “Y” is 280. Now the question comes: “Is it good or bad?”

It isn’t easy to give a straight answer to the above question on one’s attitude toward a particular object because the attitude index is a relative measure.

To conclude on a particular attitude index, it must be compared with the attitude index of competing objects, in this case, products or brands.

Functions of Attitude & Attitude Measurement

Attitudes perform four functions for the individual, viz. adjustment, value expression, ego defense, and knowledge. These functions determine an individual’s response to a particular product or service.

Consumers’ attitudes may be measured using a few techniques. Marketers in gauging consumers’ attitudes may apply these techniques. Measurement of consumers’ attitudes may help him decide on his course of action.

Functions Which Attitudes Perform for an Individual

Marketers are constantly trying to shape or reshape consumers’ attitudes to make them purchase their products. An identification of the function or functions being performed by an attitude is a prerequisite for successful attitude modification.

We have used the terms ‘function’ and ‘functions’ because any given attitude may simultaneously serve more than one function. There are four major functions that attitudes serve for an individual.

These functions are not seen as mutually exclusive. They are complementary to each other, and at times, overlapping. Daniel Katz, in his article titled “The Functional Approach to the Study of Attitudes,” identified the following four functions that attitudes perform for an individual:

Function-1: The Instrumental, Adjustive, or Utilitarian Function

This function is a recognition that people try to maximize the rewards in their external environment and minimize the negative consequences.

For example, a child develops positive attitudes toward the objects in his world, which are associated with the gratification of his needs and desires, and negative attitudes toward objects which punish him or thwart him.

Why the child does so? The answer is to help him reach the desired goals and avoid the undesirable ones.

An individual favoring a political party hoping that he will be benefited if the party assumes power is an example of an instrumental, adjustive, or utilitarian attitude.

The dynamics of attitude formation for the adjustment function depend upon present or past perceptions of the utility of the person’s attitudinal object.

Thus, an attitude’s adjustment function leads to action and may be related to the action tendency component of the tripartite or the three-component attitude model.

Function – 2: The Ego-Defensive Function

Through ego-defensive function, an individual protects himself from acknowledging the basic truths about himself or the harsh realities in his external world.

We know that individuals not only seek to make the most of their external world and what it offers, but they also expend a lot of energy on living with themselves.

Ego-defense basically includes the mechanisms of protecting one’s ego from one’s unacceptable impulses and from the knowledge of threatening forces from within, as well as reducing one’s anxieties created by such problems.

Ego-defense may also be termed as the device by which a person avoids facing either the inner reality of the kind of person he is or the outer reality of the dangers the world holds for him. These devices stem from the internal conflict with its resulting insecurities.

Defense mechanisms help the individual remove the conflicts created within and save the person from a complete disaster. They may also handicap the individual in his social adjustments and obtain the maximum satisfaction available to him from the world in which he lives.

For example, a worker who regularly quarrels with his supervisor and colleagues may act out some of his own internal conflicts.

By doing so, he may relieve himself of some of the emotional tensions which he is having. Ego-defense is related to the affective component of the three-component attitude model discussed earlier.

Through this function of an attitude, a person protects himself from others in the environment by concealing his most basic feelings and desires, which are regarded as socially undesirable.

Ego-defense may lead to the projection of one’s own weaknesses onto others or attributing shameful desires to others.

Function – 3: The Value Expression Function

Through the value expression function, an individual derives satisfaction from expressing attitudes appropriate to his values and concept.

The value expression function is central to ego psychology’s doctrines, which emphasize the importance of selfexpression, self-development, and self-realization.

By this time, you are aware that many attitudes prevent the person from revealing his true nature to himself and others.

Other attitudes also give positive expression to the external world, his central values, and the type of person he thinks of himself. This is served by the function of an attitude, which we term the ‘value expression’ function.

For example, if a person thinks of a nationalist, he will probably buy and use locally manufactured products to give others an idea of his self-image.

Marketers need to identify the values their consumers hold to develop products and design promotional campaigns that best suit the market’s values.

Function – 4: The Knowledge Function

This function is based upon the person’s need to give adequate structure to his universe. Other descriptions of this function could be an individual’s search for meaning, the need to understand, and the trend toward a better organization of perceptions and beliefs to provide clarity and consistency for him.

People acquire knowledge in the interest of satisfying specific needs or desires and giving meaning to what would otherwise be an unorganized, chaotic universe.

To understand their world, people need standards or frames of reference. Their attitudes help them to provide such standards. They do want to understand the events which impinge directly on their lives.

Knowledge function may be related to the cognitive component of the three-component attitude model. This function helps the individual in evaluating the world around him. It helps him to develop a positive or negative attitude toward the attitude object.

Determinants of Attitude Formation and Arousal Conditions concerning Type of Function

After you become aware of the functions that attitudes perform, you may be interested in knowing the origin and dynamics and the arousal conditions of attitudes.

One can make concerning attitude arousal because it depends on the excitation of some need in the individual or some relevant cue in the environment.

For example, when a man becomes hungry, he talks of food items. He may also express a favorable attitude toward a preferred food item if external stimulus cues or stimulates him.

In the following table (see next page), you are given an idea in the summary form regarding the determinants of attitude formation and arousal concerning the type of function.

| Shows the Determinants of Attitude Formation and Arousal concerning Type of Function | ||

| Function | Origin and Dynamics | Arousal Conditions |

| Adjustment | The utility of attitudinal objects in need of satisfaction. Maximizing external rewards associated with need. | 1. Activation of needs 4. Salience of cues |

| Ego-defense | Protecting against internal Conflicts and external Dangers. | 1. Posing of threats 2. Appeals to hatred and repressed impulses. 3. Rise in frustrations 4. Use of authoritarian suggestion |

| Value expression | Maintaining self-identity; enhancing favorable self-image; self-expression and selfdetermination | 1. The salience of cues associated with values. 2. Appeals to individual to reassert selfimage. 3. Ambiguities that threaten self-concept. |

| Knowledge | Need for understanding, meaningful cognitive organization, consistency, and clarity. |

|

Attitude Change And Consumer Behavior

The question arises as to how marketers can lead prospective consumers to adopt more favorable attitudes toward their products. Attitudes can be changed – but rarely easily. It is a time consuming and costly proposition to change consumers’ attitudes.

Marketers undertake a many activities to create favorable attitudes toward a new product or change negative attitudes toward an existing product. It is extremely difficult to change strongly held attitudes.

But, when marketers are faced with negative attitudes, they try to change those to be compatible with their offers. Marketers wishing to change consumers’ attitudes toward their products should take into consideration the factors that influence the formation of attitudes.

Different studies indicate that some of the attitude-forming factors cannot be changed by marketers. This is particularly true in the case of basic needs, personality characteristics, and group affiliations. Marketers may, however, change consumers’ experiences with regard to their brands.

If a marketer can identify that a significant number of consumers have negative attitudes toward an aspect of the marketing mix, he may try to change consumers’ attitudes to make them more favorable. But, this task is generally long, expensive, and difficult as well as requires a heavy promotional budget.

It is found from different studies that attitude change may follow a change in behavior. It implies that the goal of marketing may be to induce a trial purchase of the brand rather than to improve attitudes toward the brand.

When attitudes toward a firm’s products are favorable, information about the particular product is more likely to be received and have a positive impact on consumers.

But, if consumer attitudes are negative, the marketer’s tasks become more complex. It is easier to alter a the product’s size, shape, color, package, ingredients, or other characteristics to make the product better conform to the consumer’s attitude.

But, it is considerably more difficult and expensive to change consumers’ existing attitudes. “Much evidence indicates that attitude change strategies may be effective in persuading consumers to try new products or reevaluate their attitudes toward existing ones.”

The question now comes to our mind: “What is an attitude change?” Berkman and Gilson defined attitude change in the context of consumer behavior as the modification of a consumer’s evaluative inclinations toward or against any item in his or her market domain.

How May Attitudes be Changed?

How can a marketer modify consumers’ evaluative inclinations or change their attitudes? There are a number of strategies that marketers may adopt to change consumers’ attitudes.

Different models also explain techniques of attitude change that marketers may adopt. Here we shall focus on some of the important techniques of attitude change as described in a few well-known models:

Cognitive Dissonance Theory Explaining Attitude Change

It is one of the best-known and widely used theories of attitude change. Leon Festinger, a famous psychologist, proposed this theory in 1957. Dissonance denotes cognitive inconsistency. It is a situation in which two cognitions (knowledge or thoughts) are inconsistent.

Cognitive dissonance theory suggests that dissonance, want of harmony, or inconsistency occurs when an individual holds conflicting thoughts about a belief or an attitude object. Once the dissonance occurs, the individual will try to balance his cognition. That is, he will try to reduce dissonance.

By changing his attitude, he may bring cognitive consistency. If an individual is exposed to dissonance creating information, it will affect his held attitude(s), putting the person in an uncomfortable situation.

He will try to make the situation comfortable by revising or modifying old attitudes or by adopting new attitudes as well as changing the entire personal value system.

An individual may experience either internal dissonance or interattitude dissonance. Internal dissonance or intra-attitude dissonance may be created if a conflict occurs between the affective and cognitive components of an attitude.

Thus, marketers may change consumers’ attitudes by influencing their cognitions. It is done to change consumers’ beliefs about some attitude object. This may be done with the help of marketing promotional tools.

For example, suppose a group of consumers believes that a particular product brand is not good. In that case, the marketer of the said brand may develop an informative and persuasive advertisement or train his salespeople to present the brand to the customers in a way that may bring changes in their attitudes.

As customers get new information, which was not known to them, they may change their attitudes toward the brand. This may happen as consumers’ cognitions change.

Once consumers’ cognitive component of an attitude changes,, it will change their affective component. The said marketer may also try to change the feelings or the affective component of consumers’ attitudes. By presenting the brand in an emotional context, marketers may also bring changes in consumers’ attitudes.

Suppose a marketer can change any one of an attitude’s cognitive or affective components. In that case, the consumers will change the other component as they seek consistency in components of their attitudes.

Thus, marketers should always try to create dissonance in consumers’ attitudes toward competing brands if attitudes toward them are positive.

By this time, you are well aware that consumers seek consistency in the components of a given attitude if there is dissonance or inconsistency. They equally seek consistency between or among attitudes.

For example, an individual has bought a particular television brand, though he likes two other brands equally. After the purchase, he may repent for not buying one of the two other brands he liked. This situation will create dissonance between attitudes (inter-attitude dissonance).

In such a situation, the person may reduce the dissonance created between the attitudes by gathering favorable information about the brand he bought, attending to the advertisements of the purchased brand, and finding out others who have bought the same brand.

In this way, he may seek balance in his cognition and reduce his anxiety about having passed over the other brands he liked.

Situations Creating Cognitive Dissonance

Now you may be interested to know what may create dissonance in consumer cognition. Leon Festinger and Dana Bramel have identified several situations that may create cognitive dissonance in consumers. The situations are described below:

Example #1 of Cognitive Dissonance in Consumer Purchase Decisions

If a consumer buys a particular brand of a product though he liked a few others equally, he may, after the purchase is made, think that he should buy one of those brands instead of the one he bought and will experience dissonance.

Let us say he liked three brands of television almost equally but finally bought, say, brand “X” instead of brand “Y” and “Z.”

His final purchase decision to buy brand “X” may create a feeling in him that he should buy brand “Y” or brand “Z” instead of brand “X,” which will create cognitive dissonance. He may resolve such dissonance by collecting favorable information on brand “X” and screening out information about brand “Y” and brand “Z.”

Example #2 of Cognitive Dissonance in Consumer Purchase Decisions

The second situation that may create cognitive dissonance in an individual is his exposure to new information that is not consistent with his existing attitudes.

For example, a consumer regularly uses “The Colgate” brand of toothpaste, believing that it prevents decay better than any other brand of toothpaste.

Let us say that; now he comes to know from an article published in a health journal that the “Crest” brand of toothpaste is more effective in decay prevention.

This new information to which he is exposed is not consistent with his attitude toward “Colgate.” Such a situation may also create cognitive dissonance in a consumer.

Example #3 of Cognitive Dissonance in Consumer Purchase Decisions

The other situation that may create cognitive dissonance is a challenge to an individual’s attitude by opposing attitudes held by people considered important to him.

For example, an individual buys “B-Brand Milk,” pasteurized milk regularly, as he thinks this brand contains more fat than other pasteurized milk brands.

Now, if one of his relatives, a food and nutrition expert, says that the “A-Brand Milk” brand of pasteurized milk contains more fat than the “B-Brand Milk,” he will experience cognitive dissonance.

In addition to the above three situations, there could be some other situations that may create cognitive dissonance in an individual. Some of these situations are described below for your reference.

We know that an individual usually buys one of the alternative brands in a product category. After the purchase, if he finds that one or more of the rejected alternatives would be better than the one he has bought, it will create cognitive dissonance in the person.

Another situation causing cognitive dissonance is the negative factors in the purchased brand. An individual, for example, has bought a particular television brand after evaluating different brands.

After the purchase, if he finds that it takes a long time for the picture to come on the TV screen of his purchased brand, it may create cognitive dissonance in the individual.

Techniques Used in Reducing Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance, you know, creates an uncomfortable situation in the individual. He may try to reduce such dissonances in three ways, as suggested by Leon Festinger.

Thus, he may reduce the tension created by dissonance and bring harmony to his cognitions. You will now be given an idea of these ways in the following paragraphs:

You know that cognitive dissonance may be produced by conflicts developed between certain factors or factors. An individual may change such factor(s) to reduce dissonance.

Let us say an individual is experiencing dissonance between one of his attitudes and behavior. He may reduce such dissonance either by changing his attitude or behavior.

For example, Mr. Sheregul has taken a particular haircut that his family does not like. He may now either think that it is not that important what others think or may change his hairstyle the next time to make it consistent with his family’s liking.

An individual may also reduce his cognitive dissonance by seeking new information that is either consistent with his existing attitudes or behavior.

For example, an individual having dissonance in buying “Milk Vita” pasteurized milk instead of “Aarong” milk may collect information supporting his decision to buy “Milk Vita.”

He may collect such information from those who use “Milk Vita”, or find articles in newspapers or magazines advocating the “Milk Vita” brand. He may also talk to nutrition experts who speak in favor of “Milk Vita.”

In the extreme case, the individual having cognitive dissonance may think that a dissonance-creating situation is not that important.

The above-mentioned individual, for example, may think that it is all the same whether someone consumes “Milk Vita” or “Aarong” from a nutrition point of view, and thus may reduce his cognitive dissonance.

How Can a Marketer Create Cognitive Dissonance in Consumers?

A creative marketer always tries to change consumers’ attitudes either toward his brand (if existing attitudes are negative) or the competitors’ brands (if attitudes toward competitors’ brands are more favorable than the firm’s brand).

He can achieve this basically through persuasive communication. A marketer may provide consumers with information that is inconsistent with their held attitudes to create cognitive dissonance.

For example, if a group of consumers knows that brand “A” of toothpaste is more effective than brand “B,” they will hold positive attitudes toward brand “A.” Marketers of brand “B” may now provide information to consumers that may contradict their held attitudes that brand “A” is more effective.

This will create cognitive dissonance in them, and they will try to bring dissonant elements into balance.

Such information may be given through the physical product, packaging, advertising, sales promotional tools, and advocacy advertising.

The producer of brand “B” here may point in his advertisement the features of his brand that the competing brands lack.

While communicating with consumers with the aim of creating cognitive dissonance, a marketer should keep in mind a few important aspects with regard to the source it uses to communicate. They are

- The credibility of the source,

- Source likeability

- Source similarity

- Celebrity sources

- The unexpected source.

Let us now have a look at them in turn:

The credibility of the Source

A marketer may easily influence consumers’ attitudes if the source carrying the firm’s message is considered highly credible.

A source is considered credible if target consumers trust the source. A source that is thought to provide complete, objective, and accurate information is considered credible by the target consumers. Friends, neighbors, and real people or organizations are considered more credible than salespeople or advertisers.

Marketers may make their communication more trustworthy if they can encourage more of “word-of-mouth” communication because people consider this more credible than advertising communication.

This is also considered more effective because the communicator can get immediate feedback and clarify any points that are considered ambiguous.

Moreover, it is considered more reliable, and consumers consider it to offer social support and encouragement.

Source Likeability

In selecting the source of communication, marketers should emphasize selecting likable source of communication. A likable source is one that is thought of as pleasant, honest, and physically attractive. The selection of an attractive source of communication can influence consumers’ attitudes better than an unpleasant source.

Source Similarity

If the target audience considers the source of communication as similar to them in terms of physical appearance and other personal characteristics, they (the target audience) will be convinced more by communication made by such source.

Celebrity Sources

Celebrities or well-known persons are considered to be more effective sources of communication in changing consumers’ attitudes. If a renowned dentist, for example, advocates a particular brand of toothpaste, it will have more impact on users of toothpaste in changing their attitudes.

Marketers should remember that the celebrity they plan to use to advocate their products must have a resemblance with the product or service type. For example, a well-known cricketer will have a resemblance with items used in cricket games.

The Unexpected Source

It is found that unexpected communicators sometimes are more effective in changing consumers’ attitudes than expected sources.

The reasons are that they are likely to be more sincere and honest. If a well-known computer engineer, for example, advocates a particular brand of toothpaste, that is likely to have more impact on consumers’ attitudes.

Functional Theory of Attitude Change

From the earlier discussion, you know that attitudes serve four functions for an individual.

If an attitude serving a particular function changes, the individual’s attitude toward the object will also change. The functional theory of attitude change mainly focuses on how attitudes are changed with the change in functions serving attitudes.

Let us now examine how attitudes serving each of the four functions may change or modify.

Attitudes that serve an adjustment or utilitarian function may change if one of the following two conditions prevails.

First, if the attitude and activities related to this function no longer provide the satisfactions they once did.

Second, if the level of aspiration of the individual changes. The owner of a particular brand of a product who had positive attitudes toward the brand may now want a more expensive brand commensurate with his status.

The procedures for changing attitudes and behavior have little positive effect on attitudes geared toward our ego defenses because many ego-defensive attitudes are not the projection of repressed aggression but are expressions of apathy or withdrawal.

Therefore, marketing efforts to change ego-defensive attitudes may have a boomerang effect on marketers. Consideration of three basic factors, however, can help marketers change ego-defensive attitudes.

First, the removal of threats is necessary by providing a permissive and supportive atmosphere. An objective or humorous approach can serve to remove the threat.

Second, the ventilation of feelings can help to set the stage for attitude change. Providing the opportunity to talk copiously may help the subject vent his or her feelings.

Third, ego-defensive behavior can be changed as the individual acquires insight into his own mechanisms of defense. Procedures for arousing self-insight can be utilized to change behavior.

Attitudes that serve value expression functions may also be changed.

If a consumer experiences dissatisfaction with his self-concept, his value-expressive attitude will change. Two conditions are relevant in changing the value of expressive attitudes.

First, creating dissatisfaction in the individual with respect to his self-concept can bring change in his held attitudes.

Second, dissatisfaction with old attitudes as inappropriate to one’s values can also lead to attitude change.

Attitudes serving knowledge function for the consumers may also be changed.

If an individual finds his old attitudes in conflict with new experiences, he will proceed to modify his beliefs. Thus, providing information to consumers that are inconsistent with their held attitudes may bring change in the cognitive component of their attitudes.

Thus, any situation that is ambiguous for the individual will likely produce an attitude change. One’s need for cognitive structure is such that he will either modify his beliefs to impose structure or accept some new mechanisms to balance his cognition whenever there is an inconsistency.

Multiattribute Theory of Attitude Change

Martin Fishbein developed Multiattribute Theory of Attitude Change; later on, he modified his model and termed it an Extended Behavioral Intentions model.

According to the said model, a consumer’s intention to perform a specific purchasing activity is a function of the person’s beliefs and evaluation of the consequences of the buying activity.

Fishbein expressed it as:

Using the elements of this model, a marketer may pursue a number of strategies to bring changes in consumers’ attitudes toward his products. The possible strategies are:

- Change the beliefs about the attributes of the brand.

- Change the relative importance of consumer’s beliefs

- Add new beliefs

- Change the beliefs about the attributes of the ideal brand.

Let us now discuss how a marketer may apply these strategies:

If a marketer intends to change consumers’ beliefs about the brand’s attributes, he may try to shift beliefs about the brand’s performance to one or more attributes. He may make attempts to change consumers’ perceptions of the brand on one or more aspects.

When deciding to buy a particular brand of a product, consumers may consider some beliefs more important than others. Thus, marketers may try to change attitudes by shifting the relative importance from poorly evaluated to positively evaluated attributes.

If, for example, consumers believe that power consumption rate is more important in selecting a brand of television, and if the advertiser’s brand consumes more power, he can try to change consumers’ perception by focusing on the other attribute(s) that his brand possesses.

For example, he may advertise through testimonials received from experts that the life of the picture tube is a more important attribute buyer should consider when selecting a brand of television. He should make sure that his brand is better in this attribute.

The other attitude change strategy involves adding new beliefs to the consumers’ existing belief structures.

Through marketing communications, marketers may introduce a new attribute into the cognitive structure. By doing so, they can increase the overall attractiveness of their brands.

For example, a producer of a particular brand of mosquito coil may announce that his brand works for 14 hours, instead of the 10 hours, that all other brands work.

The other attitude change strategy is changing the beliefs about the attributes of the ideal brand. It involves altering the perceptions of the ideal brand. A toothpaste manufacturer, for example, may attempt to convince toothpaste users that bad taste is good in the case of toothpaste (if his brand tastes bad).

In conclusion, we can say that a marketer can change the beliefs about the attributes of a brand to change consumers’ attitudes. He may also try to change the relative importance that consumers place on these beliefs, thus can change their attitudes.

He may also try to add new beliefs to the existing attitude structure of consumers. A marketer may also try to change their beliefs about the attributes of the brand considered ideal to them. Any one of the above four strategies may bring the desired result for a marketer if the strategy is successfully applied.

Conclusion

When consumers choose products, there are several important factors that influence their decisions. These include their attitudes, self-image, and habits.

Attitudes, especially, play a major role in how consumers evaluate and select products. This makes them a crucial consideration for marketers, who can use their understanding of consumer attitudes to predict sales, analyze markets, and develop effective marketing strategies.

Attitudes are learned predispositions that involve beliefs, feelings, and behaviors. Marketers aim to create cognitive dissonance through persuasive communication to influence these attitudes. Although changing attitudes can be challenging, it is achievable by altering experiences and behaviors.

Positive attitudes result in positive responses and purchases, while negative attitudes require more complex strategies to change. Ultimately, the goal is to modify our inclinations towards products through attitude change.

- Consumer attitudes toward products and brands greatly influence their buying behavior. The success of companies depends on how consumers perceive their products.

- Consumer attitudes play a role in decision-making, learning, and purchasing. Understanding consumer attitudes helps marketers predict sales and develop new products.

- Consumer attitudes shape preferences for products, advertising, and brands.

- Product usage increases when consumers have a more favorable attitude toward it, and vice versa.

- Different brands have varying market shares due to differences in consumer attitudes.

- Marketers aim to change consumer attitudes through persuasive messages, but other factors also matter.

- Trying new products can influence consumer attitudes, so marketers reinforce positive attitudes.

- Attitude refers to consumers’ thoughts and feelings toward something, such as a product or an idea.

- Marketers seek to create positive beliefs about their products to stimulate consumer interest.

- Marketers can create uncertainty by presenting information that contradicts consumers’ existing attitudes.

- Changing consumer attitudes is challenging and costly for marketers. Certain factors, such as basic needs and personality, are not easily influenced by marketers and impact attitudes. Sometimes behavior changes first, and then attitudes follow.

- Consumers with a positive attitude toward a product pay more attention to related information. Overcoming negative attitudes can be difficult for marketers.

- Modifying the product itself is often easier than changing consumer attitudes toward it. Strategies to change attitudes can encourage consumers to try new things or reconsider existing choices.