Commercial banks are high-risk businesses that offer valuable services such as market knowledge, transaction efficiency, and funding capability. Banks use their balance sheets to facilitate transactions and absorb risks. Effective risk management is crucial to ensure solvency and maximize shareholder returns.

Let’s understand bank risk management.

Intro to Bank Risk Management

There is a risk in running a business of any kind, not to mention commercial banks. Banking businesses rather bear relatively more risk than other types of businesses. In providing financial services, they assume various kinds of financial risks.

Over the last decade, our understanding of the place of commercial banks within the financial sector has improved substantially. Amply justified to say that market participants seek the services of banks and other financial institutions because of their ability to provide;

- Market knowledge,

- Transaction efficiency, and

- Funding capability

In performing these roles, banks and other financial institutions generally act as a principal in the transaction. They use their balance sheet to facilitate the transaction and absorb its associated risks. To be sure, there are activities performed by banking firms that do not have direct balance sheet implications.

These services include agency and advisory activities such as;

- trust and investment management,

- private and public placements through “best efforts” or facilitating contracts,

- standard underwriting,

- the packaging, securitizing, distributing, and servicing of loans, primarily in consumer and real estate debt.

These items are absent from the traditional financial statement because the latter relies on generally accepted accounting procedures rather than a true economic balance sheet.

Nonetheless, most of the banking firm’s risks are in on-balance-sheet businesses. The discussion of risk management and the necessary procedures for risk management and control has centered on this area.

Accordingly, it is here that our review of risk management procedures will concentrate.

What is Risk?

Risk is defined as the volatility or standard deviation of the net cash flows of the firm.

- The risk may also be measured in terms of different financial products.

- But, the objective of the banks as a whole will be to add value to the Banks’ equity by maximizing the risk-adjusted return to shareholders.

- By contrast, for banks, risk management is their core business. So, inadequate risk management may threaten a bank’s solvency, where insolvency is defined as negative net worth.

Definition of Bank Risk Management

Risk management involves:

- Identification of the key financial risks,

- Deciding where risk exposure should be increased or

- Reduced and found methods for monitoring and managing the bank’s risk position in real-time.

The bank’s objective is to maximize profits and shareholder value-added, and risk management is central to achieving this goal. The related terminologies are:

- Shareholder value-added is earnings above an expected minimum return on economic capital.

- The minimum return is the risk-free rate plus the risk premium for the profit-maximizing firm, in this case, a bank.

- The risk-free rates refer to the rate of return on an asset, a rate of return that is granted. The risk premium depends on the perceived risk of the bank’s activities in the marketplace.

Management Perspectives of Risks

The risks contained in the bank’s principal activities, i.e., those involving its balance sheet and its basic business of lending and borrowing, are not all borne by the bank itself.

In many instances, the institution will eliminate or mitigate the financial risk associated with a transaction by proper business practices; in others, it will shift the risk to other parties through a combination of pricing and product design.

The banking industry recognizes that an institution need not engage in business in a manner that unnecessarily imposes risk upon it, nor should it absorb the risk that can be efficiently transferred to other participants.

Rather, it should only manage risks at the firm level that are more efficiently managed than by the market itself or by their owners in their own portfolios. In short, it should accept only those risks that are uniquely a part of the bank’s array of services.

All financial institutions’ risks can be segmented into three separable types from a management perspective. These are:

- risks that can be eliminated or avoided by simple business practices,

- risks that can be transferred to other participants, and,

- risks that must be actively managed at the firm level.

Risk Avoidance

In the first of these cases, the practice of risk avoidance involves actions to reduce the chances of idiosyncratic losses from standard banking activity by eliminating risks that are superfluous to the institution’s business purpose.

Common risk avoidance practices here include at least three types of actions;

- Standardizing processes, contracts, and procedures to prevent inefficient or incorrect financial decisions is the first of these.

- The construction of portfolios that benefit from diversification across borrowers and reduce the effects of any one loss experience is another.

- The third is implementing incentive-compatible contracts with the institution’s management to require that employees be held accountable.

In each case, the goal is to rid the firm of risks that are not essential to the financial service provided or absorb only an optimal quantity of a particular kind of risk.

Risk Transfer

Some risks can be eliminated, or at least substantially reduced, through the technique of risk transfer.

Markets exist for many of the risks borne by the banking firm. Interest rate risk can be transferred by interest rate products such as swaps or other derivatives. Borrowing terms can be altered to effect a change in their duration.

Finally, the bank can buy or sell financial claims to diversify or concentrate the risks that result from servicing its client base.

To the extent that the market understands the financial risks of the assets created by the firm, these assets can be sold at their fair value.

Unless the institution has a comparative advantage in managing the attendant risk and/or a desire for the embedded risk they contain, the bank has no reason to absorb such risks rather than transfer them.

Risk Management

However, there are two classes of assets or activities where the risk inherent in the activity must be absorbed at the bank level.

In these cases, good reasons exist for using firm resources to manage bank-level risk. The first of these includes financial assets or activities where the nature of the embedded risk may be complex and difficult to communicate to third parties.

This is when the bank holds complex and proprietary assets with thin if not non-existent, secondary markets.

Communication in such cases may be more difficult or expensive than hedging the underlying risk.

Moreover, revealing information about the customer may give competitors an undue advantage.

The second case includes proprietary positions that are accepted because of their risks and their expected return.

Here, risk positions that are central to the bank’s business purpose are absorbed. Credit risk inherent in the lending activity is a clear case in point, as is a market risk for the trading desk of banks active in certain markets.

In all such circumstances, the risk is absorbed and needs to be monitored and managed efficiently by the institution. Only then will the firm systematically achieve its financial performance goal.

Rationales of Risk Management

It seems appropriate for any discussion of risk management procedures to begin with why these firms manage risk. According to standard economic theory, managers of value-maximizing firms ought to maximize expected profit without regard to the variability around its expected value.

However, four distinct rationales can be offered for active risk management.

These include:

- Managerial self-interest,

- The nonlinearity of the tax structure,

- The cost of financial distress,

- Capital market imperfections.

In each case, the volatility of profit leads to a lower value for some of the firm’s stakeholders. Each of these four components is described below:

Managerial self-interest

In the first case, it is noted that managers have limited ability to diversify their investment in their own firm due to limited wealth and the concentration of human capital returns in the firm they manage. This fosters risk aversion and a preference for stability.

The non-linearity of the tax structure

In the second case, it is noted that, with progressive tax schedules, the expected tax burden is reduced by reduced volatility in reported taxable income.

The cost of financial distress

This focuses on the fact that a decline in profitability has a more than proportional impact on the firm’s fortunes. Financial distress is costly, and external financing costs increase rapidly when a firm’s viability is questioned.

Capital market imperfections

This is another reason why risk matters to the stakeholders of a firm. Any of these reasons is sufficient to motivate management to concern itself with risk and carefully assess the level of risk associated with any financial product and potential risk mitigation techniques.

Steps Of Bank Risk Management

In essence, what techniques are employed to limit and manage the different types of risk, and how are they implemented in each area of risk control? It is to these questions that we now turn.

After reviewing the procedures employed by leading firms, an approach emerges from examining large-scale risk management systems. The management of the banking firm relies on a sequence of steps to implement a risk management system. These can be seen as containing the following four parts:

- standards and reports,

- position limits or rules,

- investment guidelines or strategies, and

- incentive contracts and compensation.

These tools are generally established to measure exposure, define procedures to manage these exposures, limit individual positions to acceptable levels, and encourage decision-makers to manage risk consistently with the firm’s goals and objectives.

We elaborate on each part of the process below to see how these four parts of basic risk management techniques achieve these ends.

Step-1: Standards and Reports

The first of these risk management techniques involves two different conceptual activities, i.e., standard-setting and financial reporting. They are listed together because they are the sine qua non of any risk system.

Underwriting standards, risk categorizations, and review standards are all traditional risk management and control tools.

Consistent evaluation and rating of exposures of various types are essential to understand the risks in the portfolio and the extent to which these risks must be mitigated or absorbed.

The standardization of financial reporting is the next ingredient. Outside audits, regulatory reports, and rating agency evaluations are essential for investors to gauge asset quality and firm-level risk.

These reports have long been standardized, for better or worse. However, the need goes beyond public reports and audited statements to management information on asset quality and risk posture.

Step-2: Position Limits and Rules

A second technique for internal control of active management is position limits and/or minimum standards for participation.

In terms of the latter, the domain of risk-taking is restricted to only those assets or counterparties that pass some prespecified quality standards. Then, even for eligible investments, limits are imposed to cover exposures to counterparties and credits.

In general, each person who can commit capital will have a well-defined limit. This applies to traders, lenders, and portfolio managers. While such limits are costly to establish and administer, their imposition restricts the risk that any individual can assume and, therefore, by the organization as a whole.

Summary reports show limits as well as current exposure by business unit periodically. In large organizations with thousands of positions maintained, accurate and timely reporting is difficult but even more essential.

Step-3: Investment Guidelines and Strategies

Investment guidelines and recommended positions for the immediate future are the third technique commonly in use.

Here, strategies are outlined in terms of concentrations and commitments to particular areas of the market, the extent of desired asset-liability mismatching or exposure, and the need to hedge against the systematic risk of a particular type.

The limits described above lead to passive risk avoidance and/or diversification because managers generally operate within position limits and prescribed rules.

Beyond this, guidelines offer firm-level advice as to the appropriate level of active management, given the state of the market and the willingness of senior management to absorb the risks implied by the aggregate portfolio.

Such guidelines lead to firm-level hedging and asset-liability matching.

In addition, securitization and even derivative activity are rapidly growing position management techniques open to participants looking to reduce their exposure in line with management’s guidelines.

Step-4: Incentive Schemes

To the extent that management can enter incentive-compatible contracts with line managers and make compensation related to the risks borne by these individuals, then the need for elaborate and costly controls is lessened.

However, such incentive contracts require accurate position valuation and proper internal control systems.

Such tools include position posting, risk analysis, allocating costs, and setting risk-sharing incentive contracts to assure incentive compatibility between principals and agents.

Notwithstanding the difficulty, well-designed systems align managers’ goals with other stakeholders in the most desirable way.

Why do Banks Need Risk Management Systems?

The banking industry has long viewed the problem of risk management as the need to control four of the above risks, which make up most, if not all, of their risk exposure.

- Credit risk,

- Interest rate risk,

- Foreign exchange risk, and

- Liquidity risk.

Accordingly, the study of bank risk management processes essentially investigates how they manage these four risks (credit, interest rate, foreign exchange, and liquidity risk).

In each case, the procedure outlined above is adapted to the risk considered to standardize, measure, constrain, and manage each risk.

Beyond the basic four financial risks, viz., credit, interest rate, foreign exchange, and liquidity risk, banks have many other concerns, as indicated above.

Like operating risk and/or system failure, some are a natural outgrowth of their business, and banks employ standard risk avoidance techniques to mitigate them.

Standard business judgment is used in this area to measure the costs and benefits of risk reduction expenditures, system design, and operational redundancy.

While generally referred to as risk management, this activity substantially differs from managing financial risk.

Yet, there are still other risks, somewhat more amorphous but no less important. In this latter category are

- Legal risk

- Regulatory risk

- Suitability risk

- Reputational risk, and

- Environmental risk

Substantial time and resources are devoted to protecting the firm’s franchise value from erosion in each risk area.

As these risks are less financially measurable, they are generally not addressed formally or structured. Yet, they are not ignored at the senior management level of the bank.

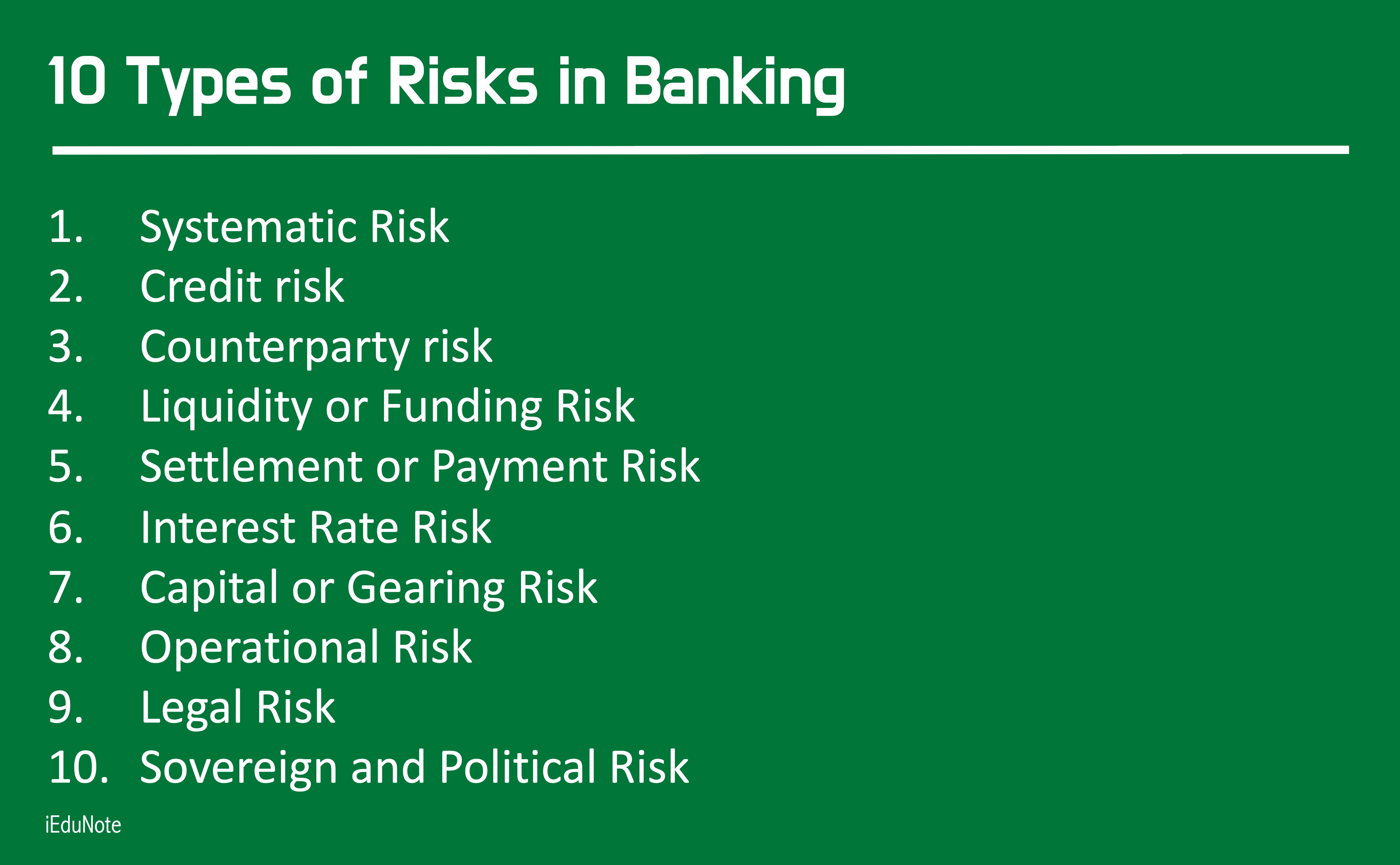

Types of Risks in Banking

Systematic Risk

- Systematic risk is the risk of asset value change associated with systematic factors. It is sometimes referred to as market risk, which is, in fact, a somewhat imprecise term.

- This risk can be hedged by its nature but cannot be diversified completely away. Systematic risk can be thought of as undiversIfiable risk.

- All investors assume this type of risk whenever assets owned or claims issued can change in value due to broad economic factors. As such, systematic risk comes in many different forms.

- However, two are of greatest concern for the banking sector: variations in the general level of interest rates and the relative value of currencies.

- Because of the banks’ dependence on these systematic factors, most try to estimate the impact of these particular systematic risks on performance, attempt to hedge against them, and thus limit the sensitivity to variations in unverifiable factors.

- Accordingly, most will track interest rate risk (discussed later) closely. They measure and manage the firm’s vulnerability to interest rate variation, even though they can not do so perfectly.

- At the same time, international banks with large currency positions closely monitor their foreign exchange risk and try to manage and limit their exposure to it.

- Similarly, some institutions with significant investments in one commodity, such as oil, through their lending activity or geographical franchise concern themselves with commodity price risk.

- Others with high single-industry concentrations may monitor specific industry concentration risks and the forces that affect the fortunes of the industry involved.

Credit risk

- Credit risk arises from non-performance by a borrower. It may arise from either an inability or an unwillingness to perform in the pre-committed contracted manner.

- This can affect the lender holding the loan contract and other lenders to the creditor. Therefore, the borrower’s financial condition and the current value of any underlying collateral are of considerable interest to its bank.

- The real risk from credit is the deviation of portfolio performance from its expected value. Accordingly, credit risk is diversifiable but difficult to eliminate. This is because some of the default risks may result from the systematic risk outlined above.

- In addition, the idiosyncratic nature of some of these losses remains a problem for creditors despite the beneficial effect of diversification on total uncertainty. This is particularly true for banks that lend in local markets and take on highly illiquid assets. In such cases, the credit risk is not easily transferred, and accurate loss estimates are difficult to obtain.

To learn more, check out our article on what credit risk is and how banks manage it.

Counterparty risk

- Counterparty risk comes from the non-performance of a trading partner.

- The non-performance may arise from the counterparty’s refusal to perform due to an adverse price movement caused by systematic factors or some other political or legal constraint that the principals did not anticipate.

- Diversification is the major tool for controlling nonsystematic counterparty risk.

- Counterparty risk is like credit risk but is generally viewed as a more transient financial risk associated with trading than standard creditor default risk.

- In addition, a counterparty’s failure to settle a trade can arise from other factors beyond a credit problem.

Liquidity or Funding Risk

- Liquidity or funding risk refers to the risk of insufficient liquidity for normal operating requirements.

- A shortage of liquid assets is often the source of the problems because the bank cannot raise funds in the retail or wholesale markets.

- Funding risk usually refers to a bank’s inability to fund its day-to-day operations. Customers place their deposits with a bank.

- The liquidity of an asset is the ease with which it can be converted to cash. A bank can reduce its liquidity risk by keeping its assets liquid. But if it is excessively liquid, its return will be lower.

To understand how the liquidity risk management process works, read our article.

Settlement or Payment Risk

- Settlement or payment risk is created if one party to a deal pays money or delivers assets before receiving its cash or assets, exposing it to potential loss.

- Settlement risk can include credit risk if one party fails to settle, liquidity risk, or a bank may not settle a transaction.

- The settlement risk is closely linked to foreign exchange markets because time zones may create a gap in the timing of payments.

Interest Rate Risk

- Interest rates are another form of price risk because the interest rate is the price of money.

- It arises due to interest rate mismatches. Bank engages in asset transformation, and their asset and liabilities differ in maturity and volume.

Capital or Gearing Risk

- U Banks are more highly geared than other businesses. There are normally no sudden or random changes in the amount people wish to save or borrow.

- Thus, the gearing limit is more critical for banks because their relatively high gearing means the threshold of tolerable risk is lower than the balance sheet.

- Banks need to increase their gearing to improve their return to shareholders.

- ROE = ROA ‘(gearing multiplier)

- ROE = Return on equity or net income/equity

- ROA = Return on assets or net income/assets

- Gearing/Ieverage multiplier = Assets/Equity

Operational Risk

The definition of operational risk varies considerably, and measuring it is more difficult. The key types of operational risk are identified as follows;

- Physical Capital

- Human Capital

- Legal

- Fraud

In fact, operational risk is associated with the problems of accurately processing, settling and taking or making delivery on trades in exchange for cash.

It also arises in record keeping, processing system failures, and compliance with various regulations. As such, individual operating problems are small probability events for well-run organizations, but they expose a firm to outcomes that may be quite costly.”

Legal Risk

- Legal risks are endemic in financial contracting and are separate from the legal ramifications of credit, counterparty, and operational risks.

- New statutes, tax legislation, court opinions, and regulations can put well-established transactions formerly into contention even when all parties have previously performed adequately and are fully able to perform in the future.

- For example, environmental regulations have radically affected real estate values for older properties and imposed serious risks to lending institutions in this area.

- The second type of legal risk arises from the activities of an institution’s management or employees. Fraud, violations of regulations or laws, and other actions can lead to catastrophic loss, as recent examples in the thrift industry have demonstrated.

Sovereign and Political Risk

Sovereign risk normally refers to the risk that a govt will default on debt owed to a bank. If a private debtor defaults, the banks will normally take possession of assets pledged as collateral.

All financial institutions face all these risks to some extent. Non-principal or agency activity involves operational risk primarily.

Since institutions, in this case, do not own the underlying assets in which they trade, systematic, credit, and counterparty risk accrues directly to the asset holder.

If the latter experiences a financial loss, however, legal recourse against an agent is often attempted. Therefore, institutions engaged in hanking would also list regulatory and reputational risks in their concerns.

Nonetheless, all would recognize the first four as key and devote most of their risk management resources to constraining these key exposure areas.

Only agency transactions bear some legal risk, if only indirectly.

However, our main interest centers around the businesses where the bank participates as a principal, i.e., intermediary. In these activities, principals must decide how much business to originate and how much to finance, sell, and contract to agents.

In so doing, they must weigh both the return and the risk embedded in the portfolio. Principals must measure the expected profit and evaluate the prudence of various risks enumerated to ensure that the result maximizes shareholder value.

Financial Derivatives & Bank Risk Management

Types of Financial Derivatives:

The key derivatives are:

- Futures.

- Forwards.

- Options.

- Swaps.

Futures

Obliges trades to purchase or sell an asset at an agreed-upon price on a specific future date

- The long position is held by the trader who commits to purchase.

- The short position is held by the trader who commits to sell.

Forwards

An arrangement calling for future delivery of an asset at an agreed-upon price The agreement to buy or sell based on exchange rates established today for settlement in the future. Banks can earn income from forwards by taking positions.

Options

A right but not an obligation to engage in the future or forward transaction.

- The call option is the right to buy an asset at a specified exercise price on or before a specific expiration date.

- The put option is the right to sell an asset at a specified exercise price on or before a specific expiration date.

Swaps

The exchange between two securities or currencies. One type of swap involves the sale (purchase) of a foreign currency with a simultaneous agreement to repurchase or sell it. The swap rate is the difference between the sale or purchase price and the price to repurchase or sell it in a swap.

Why do Banks Use Derivatives For Bank Risk Management?

- Hedge against risk arising from proprietary trading.

- Use for speculative purposes or proprietary trading.

- By using an interest rate swap, the cost of corporate borrowing can offer to be reduced.

- Generate business related to transferring various risks between different parties.

- Banks dealing in derivatives are exposed to market risk whether traded on established exchanges.

- Manage their market and credit risk caused by on or off-balance sheet activities.

Aggregation and the Knowledge of Total Exposure

Thus far, the techniques used to measure, report, limit, and manage the risks of various types have been presented. In each of these cases, a process has been developed or at least has evolved into measuring tire risk considered, and techniques have been deployed to control each of them.

The extent of the differences across risks of different types is quite striking. The credit risk process is a qualitative review of the performance potential of different borrowers. It results in a rating, periodic re-evaluation at reasonable intervals through time, and ongoing monitoring of various exposure measures.

Interest rate risk is usually measured weekly using on and off-balance sheet exposure. The position is reported in repricing terms, using gap and effective duration, but the real analysis is conducted with the benefit of simulation techniques. Limits are established, and synthetic hedges are taken based on these cash flow earnings forecasts.

Foreign exchange or general trading risk is monitored in real-time with strict limits and accountability. Here again, the effects of adverse rate movements are analyzed by simulation using ad hoc exchange rate variations and/or distributions constructed from historical outcomes.

On the other hand, liquidity risk is often dealt with as a planning exercise, although some reasonable work is done to analyze the funding effect of adverse news.

The analytical approaches subsumed in each of these analyses are complex, difficult, and not easily communicated to non-specialists in the risk considered.

The bank, however, must select appropriate levels for each risk and select, or at least articulate, an appropriate level of risk for the organization as a whole. How is this being done?

- The simple answer is “not very well.” Senior management often is presented with a myriad of reports on individual exposures, such as specific credits and complex summaries of the individual risks, as outlined above.

- The risks are not dimensioned in similar ways. Management’s technical expertise to appreciate the true nature of the risks themselves and the analyses conducted to illustrate the bank’s exposure is limited.

- Accordingly, the managers of specific risks have gained increased authority and autonomy over time.

- In light of recent losses, however, tilings are beginning to change. At the organizational level, overall risk management is being centralized into a Risk Management Committee headed by someone designated as the Senior Risk Manager.

- This institutional response aims to empower one individual or group with the responsibility to evaluate overall firm-level risk and determine the bank’s best interest as a whole.

- At the same time, this group holds line officers more accountable for the risks under their control and the institution’s performance in that risk area.

- Activity and sales incentives are replaced by performance compensation based on business volume and overall profitability. At the analytical level, aggregate risk exposure is receiving increased scrutiny.

- To do so, however, requires the summation of the different types of risks outlined above. This is accomplished in two distinct but related ways. The first of these, pioneered by Bankers Trust, is the RAROC (Risk-Adjusted Return on Capital) system of risk analysis.

- In this approach, the risk is measured in terms of the variability of outcome. Where possible, a frequency distribution of returns is estimated from historical data, and the standard deviation of this distribution is estimated.

- Capital is allocated to activities as a function of this risk or volatility measure. Then, the risky position is required to carry an expected rate of return on allocated capital, which compensates the firm for the associated incremental risk.

- The risk is aggregated and priced in the same exercise by dimensioning all risks in terms of loss distributions and allocating capital by the volatility of the proposed activity.

- A second approach is similar to the RAROC but depends less on a capital allocation scheme and more on the implied risky position’s cash flow or earnings effects. When employed to analyze interest rate risk, this was referred to as the Earnings At Risk methodology above. When market values are used, the approach becomes identical to the VaR methodology employed for trading exposure.

- This method can be used to analyze total firm-level risk similarly to the RAROC system. Again, a frequency distribution of returns for any one type of risk can be estimated from historical data.

- Extreme outcomes can then be estimated from the tail of the distribution. A worst-case historical example is used for this purpose, or a one- or two-standard deviation outcome is considered.

- Given the downside outcome associated with any risk position, the firm restricts its exposure. In the worst-case scenario, the bank does not lose more than a certain percentage of current income or market value.

- Therefore, rather than moving from value volatility through capital, this approach goes directly to the current earnings implications from a risky position.

- The approach, however, has two undeniable shortcomings. If EaR is used, it is cash flow-based rather than market value-driven. And in any case, it does not directly measure the total variability of potential outcomes through a priori distribution specification.

- Rather it depends upon a subjectively pre-specified range of risky environments to drive the worst-case scenario.

- Both measures, however, attempt to treat the issue of trade-offs among risks, using a common methodology to transform the specific risks into firm-level exposure. In addition, both can examine the correlation of different risks and the extent to which they can or should be viewed as offsetting.

- As a practical matter, however, most, if not all, of these models do not view this array of risks as a standard portfolio problem. Rather, they separately evaluate each risk and aggregate total exposure by simple addition.

- As a result, much is lost in the aggregation. Perhaps over time, this issue will be addressed.

Scope for Further Research in Bank Risk Management

The banking industry is clearly evolving to a higher level of risk management techniques and approaches than had been in place in the past.

Yet, as this review indicates, there is significant room for improvement. Before the potential value-added areas are enumerated, it is worthwhile to reiterate an earlier point.

The risk management techniques reviewed here are not the average but the techniques used by firms at the higher end of the market. The risk management approaches at smaller institutions and larger but relatively less sophisticated ones are less precise and significantly less analytic.

In some cases, they would need substantial upgrading to reach the level of those reported here. Accordingly, our review’ should be viewed as a glimpse at best practices, not average practices.

Nonetheless, the techniques employed by those defining the industry standard could improve. By category, recommended areas where additional analytic work would be desirable are listed below.

Credit Risk

The evaluation of credit rating continues to be an imprecise process. Over time, this approach needs to be standardized across institutions and borrowers.

In addition, its rating procedures need to be made compatible with rating systems elsewhere in the capital market. Credit losses, currently vaguely related to credit rating, need to be closely tracked. Credit pricing, credit rating, and expected loss should be demonstrably closer to the bond market.

However, the industry currently does not have a sufficiently broad database on which to perform the migration analysis that has been studied in the bond market.

The issue of optimal credit portfolio structure warrants further study. In short, analysis is needed to evaluate the diversification gains associated with careful portfolio design.

Currently, banks appear to be too concentrated in idiosyncratic areas and not sufficiently managing their credit concentrations by either industrial or geographic areas.

Interest Rate Risk

While simulation studies have substantially improved upon gap management, the use of book value accounting measures and cash flow losses remain problematic.

Movements to improve this methodology will require increased emphasis on market-based accounting. However, such a reporting mechanism must be employed on both sides of the balance sheet, not just the asset portfolio.

The simulations must also incorporate the advances in dynamic hedging used in complex fixed-income pricing models. As it stands, these simulations tend to be rather simplistic, and scenario testing rather limited.

Check out our article on how banks manage interest rates.

Foreign Exchange Risk

The VaR approach to market risk is a superior tool. Yet, much of the hanking industry uses an ad hoc approach to setting foreign exchange and other trading limits.

Our article on foreign exchange risk management shows; this approach can and should be used to a greater degree than it is currently.

Liquidity Risk

Crisis models need to be better linked to operational details. In addition, the usefulness of such exercises is limited by the realism of the environment considered. If liquidity risk is to be managed, the price of illiquidity must be defined and built into illiquid positions. While some institutions have adopted this logic, liquidity pricing is not commonplace.

Other Risks

As banks move more off-balance sheets, the implied risk of these activities must be better integrated into overall risk management and strategic decision-making. Currently, they are ignored when bank risk management is considered.

Aggregation of Risks

Much discussion has been of the RAROC and VaR methodologies to capture total risk management. Yet, the decisions to accept risk and the pricing of the risky position are frequently separated from risk analysis.

If the aggregate risk is controlled, these parts of the process must be better integrated within the banking firm. Both aggregate risk methodologies presume that the time dimensions of all risks can be viewed as equivalent.

Trading risk is similar to credit risk, for example. This appears problematic when market prices are not readily available for some assets and the time dimensions of different risks are dissimilar. Yet, thus far, no firm has adequately addressed this issue.

Finally, operating such a complex management system requires significant knowledge of the risks considered and the approaches used to measure them. It is inconceivable that Boards of Directors and even most senior managers have the level of expertise necessary to operate the evolving system.

Yet government regulators seem to have no idea of the level of complexity and attempt to increase accountability even as the requisite knowledge to control various parts of the firm increases.

Bankers Liability

Bankers’ liability claims have arisen as a part of a “new, growing consumerism against banks” that manifests itself in a conflict between the interests of the lender and those of the borrower firm and its owner.

A review of banker liability cases demonstrates that borrowers are not only being released from their obligations to the bankers but are also being awarded, by judge and jury alike, both compensatory and punitive damages.

Generally, bankers’ liability litigation arises from the conduct of bankers in negotiating and administering loans rather than from mistakes in the loan documents themselves. The conduct of bankers commonly serves as a factual basis for legal action when;

- bankers become highly involved in the management and operations of the borrower’s businesses,

- bankers fail to honor loan commitments or impose new terms,

- bankers commence litigation against borrowers for nonmonetary defaults,

- bankers improperly accelerate demand notes,

- bankers substitute a stronger borrower for a weaker one in connection with a loan for a failing business or property, and

- bankers are perceived to have broken promises or made untrue statements.

Borrowers must often assert banker liability claims as counterclaims in response to collection actions brought by bankers.

However, as a legal cause of action, the term “banker liability” does not denote any particular theory of liability.

Rather, claimants against bankers employ traditional legal theories in a new fashion to redress perceived injustices in the lending relationship.

The legal theories under which borrowers commence litigation include various common law causes of action (including fraud, misrepresentation, economic duress, breach of contract, and tortious interference) and several statutory prescriptions (including environments, antitrust, racketeering, and banking statutes.

Bankers can avert lawsuits or mitigate their effects by following a few basic, precautionary steps. Of course, many defenses are available to bankers within this same body of law.

Nevertheless, there is no substitute, legal or otherwise, for ordinary common sense on the part of bankers. We briefly introduce bankers’ liability and a few “pearls of wisdom.” These are:

Compliance with Agreements

- Did the bankers act in full compliance with the expressed terms of the documents governing the loans?

- Were the taros of the document modified or waived by the subsequent writings, statements, or conduct?

- Do loan documents unambiguously give the banker the right to terminate funding or to demand payments? Is this right, consistent with the other terms of the loan?

- Did the borrower breach any contractual covenants or conditions in the documents?

- If so, can the breach be established by objective criteria?

Compliance with the Duty of Good Faith and Fair Dealing

- Assuming the bankers terminated funding, did they give the borrower reasonable notice of its intent?

- Was the borrower afforded a reasonable opportunity to obtain alternative financing?

- Did objective criteria support the bankers’ action?

- Was the bankers’ action consistent with its institutional policies for terminating funding?

- Did the bankers cause the borrower to believe that additional funds would be forthcoming?

- Did the borrowers act in reasonable reliance and to its detriment on the anticipated financing?

- Has a relationship of trust or confidence been established between the bankers and borrowers?

- Did the bankers routinely offer advice or suggestions to the borrower?

- Is there a disparity of sophistication or bargaining power between the parties?

Domination and Control

- If the terms of the loan give the bankers broad power concerning the management and operations of the debtor, did the banker improperly exercises such control?

- Has the banker’s involvement merely consisted of its legitimate right to monitor the debtor’s business and collect its debt, or has the banker, in effect, been running its operations?

- Are the bankers actively participating in the day-to-day business management, or does the banker merely possess “veto power” over certain business decisions?

- Are the bankers the sole or primary source of credit for the borrower?

- Did the bankers wrongfully use threats to control the borrower’s conduct?

- Do the bankers control a substantial amount of the debtor’s stock?

- All factors indicative of control, taken together, constitute sufficient control to rise to the level of domination for the instrumentality rule or the doctrine of equitable subordination.

- If so, can the bankers satisfy the higher standard of care required of fiduciaries?

Minimizing Bank’s Risk of Lawsuits

The banker should take the following steps to reduce the risk of a lawsuit:

- Prepare memos to the file properly, leaving out epithets, vulgarisms, and threats.

- Ensure the parties clearly understand any deal struck, avoiding side agreements and oral “explications,” if possible. Writing a self-serving memo to the file can be helpful, outlining the specifics.

- Use appropriate documentation reflective of the actual transaction.

- Avoid imposing excessively harsh terms not intended for use (such as waiver of jury trial or management control provisions).

- Review the bank’s loan manuals and the borrower’s credit evaluations, remembering either, or both may be read to the jury.

- Avoid personality conflict, immediately removing officers who could be accused of acting prejudicially or unfairly.

- Pack up your troubles in an old kit bag, and leave them with the attorneys.

When the banker does find a problem loan, they should take the following steps before it’s too late:

- Review the file for all the facts.

- Audit all loan documents.

- Interview all the personnel involved.

- Assess the borrower’s motivation to settle rather than to sue.

- Look for enforcement alternatives to filing a lawsuit. Will give a little to a restructuring gain a lot, such as collateral, new guarantees, or time to overcome adverse conduct courses?

- Review all waivers the bank might have given, whether in writing or orally.

- Provide ample notice of bank action (including demand, and setoff) when that is at all practical. If working toward deadlines, make sure the borrower clearly understands them. Put them in writing if possible.

- Work with good attorneys, called in as soon as practicable. Reliance on the advice of counsel may demonstrate good faith, adding to the chances of a successful defense.

- Never use it for small sums or spite. Consider the advisability of suing when the borrower can’t pay at all and the amount is quite large.

- Always be businesslike by avoiding abusive language, harshness, and table pounding.

- Management changes can be effected when necessary but require care to accomplish without liability.

- Let the borrower and its advisers be the source of business plans, not the bank.

- Finally, after doing the climb-up loan Workout Mountain, you’ll receive the ten commandments of the workout cycle as a banker.

The Ten Commandments of the Workout Cycle:

- Thou shalt watch for early warning signs of trouble.

- Thou shalt get all of the facts.

- Thou shah bring a workout specialist to conduct the workout negotiations.

- Thou shalt not waive any rights.

- Thou shalt look at all of the alternatives before commencing workout discussions.

- Thou shalt always look at both sides of the issue.

- Thou shalt involve as many people as possible in workout discussions.

- Thou shalt be honest.

- Thou shalt not be arrogant.

- Thou shalt take what you can get.

Conclusion

Over the last decade, our understanding of commercial banks within the financial sector has improved substantially.

The overwhelming majority of the risks facing the banking firm are in on-balance-sheet businesses. The discussion of risk management and the necessary procedures for risk management and control has centered on this area.

There are two classes of assets or activities where the risk inherent in the activity must be absorbed at the bank level.

The management of the banking firm relies on a sequence of steps to implement a risk management system. Accordingly, it is here that our review of risk management procedures will concentrate.

These can be seen as containing the following four parts:

- Standards and reports.

- Position limits or rules,

- investment guidelines or strategies, and

- incentive contracts and compensation.

These tools are generally established to measure exposure, define procedures to manage these exposures, limit individual positions to acceptable levels, and encourage decision-makers to manage risk consistently with the firm’s goals and objectives.