What is Causal Research or Causal Studies?

Causal research, also called causal study, an explanatory or analytical study, attempts to establish causes or risk factors for certain problems.

Our concern in causal studies is to examine how one variable ‘affects’ or is ‘responsible for changes in another variable. The first variable is the independent variable, and the latter is the dependent variable.

Examples of Causal Research or Causal Studies

While no one can ever be certain that variable A (say) causes variable B (say), one can gather some evidence that increases the belief that A leads to B.

Examine the following queries and try to guess if there is any association between A and B:

- Is there a predicted co-variation between A and B? Do we find that A and B occur in the way we hypothesized? When A does not occur, is there also an absence of B? Or when there is less of A, does one find more or less of B? When such conditions of covariance exist, it indicates a possible causal connection between A and B.

- Is the time order of events moving in the hypothesized direction? Does A occur before B? If we find that B occurs before A, we can have little confidence that causes.

- Is it possible to eliminate other possible causes of B? Can we determine that C, D, and E do not co-vary with B in a way that suggests possible causal connections?

Types of Causal Research

- Comparative Study

- Case-Control Study

- Cohort Study

Comparative Study

This is a study that has its main focus on comparing as well as describing groups.

In a study of malnutrition, for example, the researcher will not only describe the prevalence of malnutrition, but by comparing malnourished or well-nourished children, he will try to determine which socio-economic behavior and other independent variables have contributed to malnutrition.

In analyzing the results of a comparative study, the researcher must watch out for confounding or intervening variables that may distort the true relationship between the dependent and independent variables.

Case-Control Study

A case-control study is a retrospective study that looks back in time to find the relative risk between a specific exposure (e.g., second-hand tobacco smoke) and an outcome (e.g., cancer).

The investigator compares one group of people with the problem, the cases, with another group without a problem or who did not experience the event, called a control group or comparison group.

The goal is to determine the relationship between risk factors and disease or outcome and estimate the odds of an individual getting a disease or experiencing an event.

Case-control studies have four main steps:

- The study begins by enrolling people with a certain disease or outcome.

- A second control group of similar size is sampled, preferably from a population identical in every way except that they don’t have the disease or condition being studied. They should not be selected because of their exposure status.

- People are asked about their risk exposure.

- Finally, an odds ratio is calculated.

In an epidemiological study, we find the exposure of each subject to the possible causative factor and see if this differs between the two groups. We cite an example here.

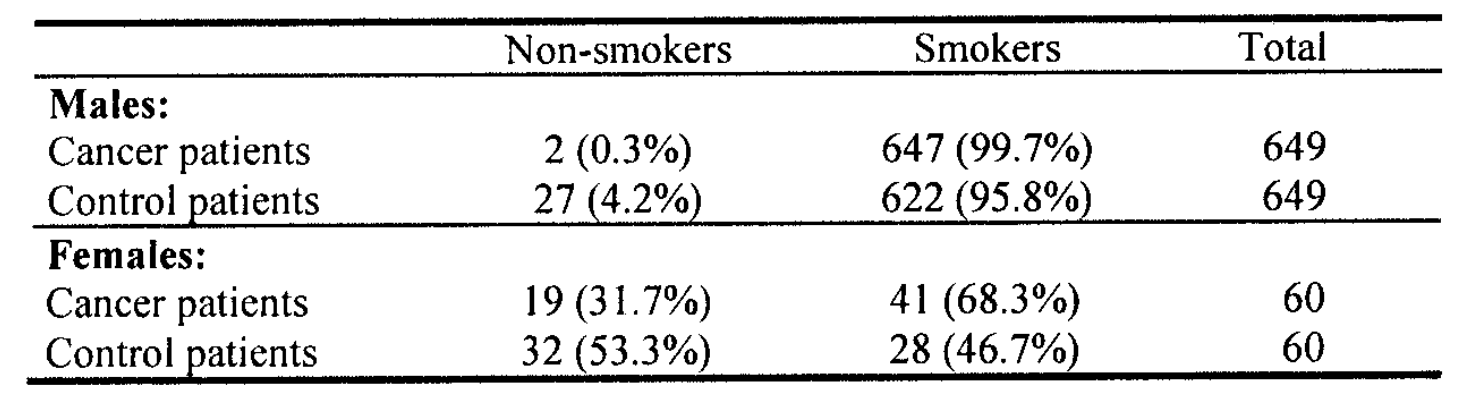

Doll and Hill (1950) carried out a case-control study into the etiology of lung cancer. Twenty London hospitals notified all patients admitted with carcinoma of the lung, the cases.

An interviewer visited the hospital to interview the cases, and at the same time, selected a patient with a diagnosis other than cancer, of the same sex, and within the same 5-year age group as the case, in the same hospital, at the same time, as control.

The accompanying table shows these patients’ relationship between smoking and lung cancer. A smoker was anyone who had smoked as much as one cigarette a day for as much as one year.

It appears that cases were more likely than controls to smoke cigarettes. Doll and Hill concluded that smoking is important in developing lung carcinoma.

The case-control study is an attractive method of investigation because of its relative speed and cheapness compared to other approaches.

However, there are difficulties in selecting the cases, selecting the controls, and obtaining the data. The matching of cases and controls has to be done with care.

There are difficulties, too in interpreting the results of a case-control study.

One is that case-control study is often retrospective; that is, we start with the present disease state, e.g., lung cancer, and relate it to the past, e.g., history of smoking. We may rely on the unreliable memories of the

subjects. This may lead both to random error among cases and controls and systematic recall bias, where one group, usually the cases, recalls events better than the others.

Cohort Study

In a cohort study, also called a prospective study, we take a group of people, the cohort, and observe whether they have the suspected causal factor.

We then follow them over time and observe whether they develop the disease. This is a prospective study, as we start with the possible cause and see whether this leads to the disease in the future.

It is also longitudinal, meaning that subjects are studied more than once. A cohort study usually takes a long time, as we must wait for future event to occur. It involves keeping track of large numbers of people, sometimes for many years.

Often it becomes necessary to include a large number of people in the sample to ensure that sufficient numbers will develop the disease to enable comparisons between those with and without the factor.

A study may start with one large cohort.

After the cohort is selected, the researcher may determine who is exposed to the risk factor (e.g., smoking) and who is not and follow the two groups over time to determine whether the study group develops a higher prevalence of lung cancer than the control group.

Suppose it is impossible to select a cohort and divide it into a study group and a control group. In that case, two cohorts may be chosen, one in which the risk factor is present (study group) and one in which it is absent (control group).

In all other respects, the two groups should be as alike as possible.

The control group should be selected simultaneously as the study group, and both should be followed with the same intensity.

Cohort studies are the only sure way to establish causal relationships.

However, they take a fairly long time than the case-control studies and are labor-intensive and, therefore, expensive.

The major problem is usually related to identifying all cases in a study population, especially if the problem has a low incidence. The other problem is the problem of ‘censoring’ due to the inability to follow up with all persons included in the study over several years because of population movements or death.

The major difference between a case-control study and a cohort study is that in a case-control study, we select by problem status and look back to see what, in the past, might have caused the problem.

In contrast, we wait to see whether the problem develops in a cohort study. The following diagrams represent the two types of study.

The example below distinguishes the cohort study from case-control and comparative studies.

Example of Cohort Study

Suppose we anticipate a causal relationship between using a certain water source and the incidence of diarrhea among children under 5 years of age in a village with different water sources.

You can select a group of children under 5 years and check at regular intervals (e.g., every 2 weeks) whether the children have had diarrhea and how serious it was.

Children using the suspected source and those using other water supply sources will be compared with the incidence of diarrhea.

This example illustrates a cohort study.

Or

You may compare children who present themselves at a health center with diarrhea (cases) during a particular period with children presenting themselves with other complaints of roughly the same severity, for example, with acute respiratory infections (controls) during the same time, and determine which source of drinking water they had used.

This example illustrates a case-control study.

Or

You could interview mothers to determine how often their children have had diarrhea during, for example, the past month, obtain information on their drinking water sources, and compare the source of drinking water of children who did and did not have diarrhea.

This is a comparative, also called a cross-sectional comparative study.

Conclusion

What is the primary objective of causal research?

Causal research, also known as a causal study or an explanatory or analytical study, aims to establish causes or risk factors for certain problems.

In causal studies, how are the variables categorized?

In causal studies, one variable is termed the independent variable, which ‘affects’ or is ‘responsible for changes in’ another variable, known as the dependent variable.

What are the three main types of causal research?

The three main types of causal research are Comparative Study, Case-Control Study, and Cohort Study.

What are the key questions to consider when determining a causal connection between two variables, A and B?

To determine a causal connection, one should consider if there’s a predicted co-variation between A and B, if the time order of events moves in the hypothesized direction with A occurring before B, and if other possible causes of B can be eliminated.

How does a Comparative Study function in causal research?

A Comparative Study focuses on comparing and describing groups. It describes a particular phenomenon and tries to determine which independent variables have contributed to it by comparing different groups.

What is the primary goal of a Case-Control Study?

A Case-Control Study is a retrospective study that looks back in time to find the relative risk between a specific exposure and an outcome. It compares a group of people with a problem (cases) to another group without the problem (controls) to determine the relationship between risk factors and the disease or outcome.

How does a Cohort Study differ from other types of causal research?

A Cohort Study, also known as a prospective study, observes a group of people (the cohort) to see if they have the suspected causal factor and then follows them over time to observe if they develop the disease. It is longitudinal and starts with the possible cause to see if it leads to the disease in the future.