What is Delegation of Authority?

What is Delegation of Authority?

A delegation of authority may be specific or general, written or unwritten. If the delegation is unclear, a manager may not understand the nature of the duties or the results expected.

For example; the job assignment of a company controller may specify such functions as accounting, credit control, and cash control, financing, export-license handling, and preparation of financial statistics, and these broad functions may even be broken down into more definite duties.

Or a controller may be told merely that he or she is expected to do what controllers generally do.

Specifically, written delegations of authority are extremely helpful both to the manager who receives them and to the person who delegates them.

The latter will more easily see conflicts or overlaps with other positions and will also be better able to identify those things for which a subordinate can and should be held responsible.

The fear that specific delegations will result in inflexibility is best met by developing a tradition of flexibility. It is true that if authority delegations are specific, a manager may regard his or her job as a staked claim with a high fence around it.

But this attitude can be eliminated by making necessary changes in the organization structure.

Much of the resistance to change through definite delegations comes from managerial laziness and the failure to reorganize things often enough for the smooth accomplishment of objectives.

Simple as a delegation of authority might appear to be, studies show that managers fail more often because of poor delegation than of any other cause.

For anyone going into any kind of organization, it is worthwhile to study the science and art of delegation.

The primary purpose of delegation is to make the organization possible.

Just as no one person in an enterprise can do all the tasks necessary for accomplishing group purpose, it is impossible, as an enterprise grows, for one person to exercise all the authority for making decisions.

As was discussed under the subject of the span of supervision, there is a limit to the number of person managers can effectively supervise and for whom they can make decisions.\

How Authority is Delegated in Organizational Hierarchy

Once this limit is crossed, the authority must be delegated to subordinates, who will make decisions within the area of their assigned duties.

Authority is delegated when discretion is vested in a subordinate by a superior.

Clearly,

Superiors cannot delegate authority that they do not have, whether they are board members, presidents, vice-presidents, or supervisors.

Equally clear, superiors cannot delegate all their authority without, in effect, passing on their position to their subordinates.

Authority Delegation Process

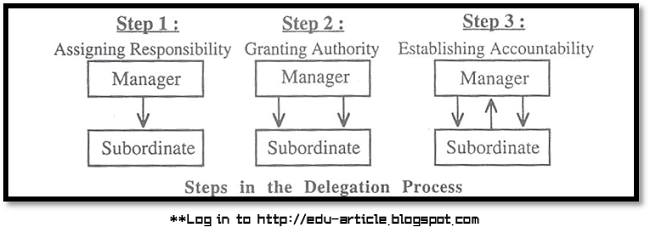

The delegation process involves three steps:

- The Superior assigns responsibility, or gives the subordinate a job to do;

- Along with the job” assignment, the subordinate is also given the authority to do the job;

- Finally the superior establishes the subordinate’s accountability— that is the subordinate attempts an obligation to carry out the task assigned by the superior.

These three steps do not occur mechanically, however indeed, when a manager and a subordinate have developed a good working relationship, the major parts of the process may be implied rather than stated.

The manager may simply mention that a particular job must be done.

A perceptive subordinate may realize that the manager is actually assigning the job to him.

From vast experience with the boss, he may also understand, without being told, that he has the necessary authority to do the job and that he is accountable to the boss for finishing the job as “agreed”.

7 Principles of Delegation of Authority

The following principles are guides to a delegation of authority.

Unless carefully recognized in practice, delegation may be ineffective, the organization may fail, and poor managing may result.

- Principle of delegation by results expected.

- Principle of a functional definition.

- Scalar principle.

- Authority-level principle.

- Principle of unity of command.

- The principle of absoluteness of responsibility.

- The principle of parity of authority and responsibility.

The delegation of authority principles are explained below;

1. Principle of delegation by results expected

Since authority is intended to furnish managers with a tool, for so managing as to assure that objective are achieved, the authority delegated to individual managers should be adequate to assure their ability to accomplish expected results.

Too many managers try to partition and define authority on the basis of the rights to be delegated or withheld, rather than to look first at the goals to be achieved and then to determine how much discretion is necessary to achieve them.

In no other way can a manager delegate authority than in accordance with the responsibility exacted.

Often a superior has some idea, vague or fixed, as to what is to be accomplished, but does not trouble to determine whether the subordinate has the authority to do it.

Sometimes superiors do not want to admit how much discretion it takes to do a job, and are reluctant to define the results expected.

2. Principle of a functional definition

To make delegation possible, activities must be grouped to facilitate accomplishment of goals, and managers of each subdivision must have authority to co-ordinate its activities with the organization as a whole.

These requirements give rise to the principle of functional definition; the more a position or a department has clear definitions of results expected, activities to be undertaken, the organizational authority delegated, and authority and informational relationships with other positions understood, the more adequately the individuals responsible can contribute towards accomplishing enterprise objectives.

To do otherwise is to risk confusion as to what is expected of whom.

Although simple as a concept, this principle which is a principle of both delegation and departmentalization is often difficult to apply.

To define a job and delegate authority to do it requires, in most cases, patience, intelligence, and clarity of objectives and plans. It is obviously difficult to define a job if the superior does not know what results are desired.

3. Scalar principle

The scalar principle refers to the chain of direct authority relationships from superior to subordinate throughout the organization.

The clearer the line of authority from the top manager in an enterprise is to the subordinate position, the more effective the responsible decision-making and organization communication will be.

A clear understanding of the scalar principle is necessary for proper organization functioning. Subordinates must know who delegates’ authority to them and to who matters beyond their own authority must be referred.

Although the chain of command may be safely departed from for purposes of information, departures for purposes of decision-making tend to destroy the decision-making system and undermine manager-ship itself.

4. Authority-level principle

Functional definition plus the scalar principle gives rise to the authority level principle. Clearly, at some organization level, authority exists for making a decision within the power of an enterprise.

Therefore, the authority-level principle derived would be as follows; maintenance of intended delegation requires that decisions within the authority of individuals be made by them and not be referred upwards in the organization structure.

In other words, managers at each level should make whatever decisions they can in the light of their delegated authority, and only matters that authority limitations keep them from deciding should be referred to superiors.

5. Principle of unity of command

A basic management principle often disregarded for what are believed to be compelling circumstances, is that of the unity of command: the more completely an individual has a reporting relationship to a single superior, the less the problem of conflict in instructions and the greater the feeling of personal responsibility for results.

In discussing delegation of authority, it has been assumed that the right of discretion over a particular activity will flow from a single superior to a subordinate.

Although it is possible for a subordinate to receive authority from two or more superiors and logically possible to be held responsible by them, the practical difficulties of serving two or more masters are obvious.

An obligation is essentially personal, and authority delegation by more than one person to an individual is likely to result in conflicts in both authority and responsibility.

6. The principle of absoluteness of responsibility

Since responsibility, being an obligation owed, cannot be delegated, no superior can escape, through delegation, responsibility for the activities of subordinates, for it is the superior who has delegated authority and assigned duties.

Likewise, the responsibility of subordinates to their superiors for performance is absolute, once they have accepted an assignment and the right to carry it out, and superiors cannot escape responsibility for the organization activities of their subordinates.

7. The principle of parity of authority and responsibility

Since authority is the discretionary right to carry out assignments and responsibility is the obligation to accomplish them, it logically follows that authority should correspond to responsibility.

From this rather obvious logic is derived the principle that responsibility for an action cannot be greater than that implied by authority delegated, nor should it be less.

The president of a firm may, for example, assign duties to the manufacturing vice-president, such as buying raw materials and machine tools and hiring subordinates in order to achieve certain goals.

The vice-president will be unable to perform these duties unless given enough discretion to meet this responsibility.

Managers often try to hold subordinates responsible for duties for which they do not have the necessary authority to perform.

This is, of course, unfair.

Sometimes sufficient authority is delegated, but the delegate is not held responsible for its proper use.

This is, obviously, a case of poor managerial direction and control, and has no bearing upon the principle of parity.

5 Guides for Overcoming Weak Delegation in Organization

Unclear delegations, partial delegations, delegations inconsistent with the results expected, and the hovering of superiors who refuse to allow subordinates to use their authority are among the many widely found weaknesses of the delegation of authority.

Combine with these weaknesses untrained, inept, or weak subordinates, who go to their bosses for decisions and the shirking subordinates, who will not accept responsibility.

Add to these, the lack of plans, planning information, and incentives, and then all these together will partly explain the failure of delegation.

It shows, as is so generally the case in managing, that delegation does not stand alone but is related to other aspects of the whole system of managing.

But most of the responsibility for weak delegation lies with superiors and, primarily, with top managers.

In overcoming these errors—and emphasizing the principles outlined above—the five following guides are practical in making delegation effective;

- Define assignments and delegate authority in the light of results expected.

- Select the person in the light of the job to be done. This is the purpose of the managerial function of staffing. It is important to remember that qualifications influence the nature of the authority delegated.

- Maintain open lines of communication. This means that there should be a free flow of information between the superior and the subordinate, and subordinates should be furnished with information with which to make decisions and properly interpret the authority delegated.

- Establish proper controls. But if controls are not to interfere with the delegation, they must be relatively broad and designed to show deviations from plans rather than interfere with detailed actions of subordinates.

- Reward effective delegation and successful assumption of authority. It is seldom sufficient to suggest that authority be delegated, or even to order that this is done. Managers should be ever watchful for means of rewarding both effective assumptions of authority.

Although many of these rewards will be in terms of money, the granting of greater discretion and prestige—both in a given position and in promotion to a higher position—often works as a stronger incentive.