The organizational structure indicates the formal relationship between the employees and employers, the systems of tasks, workflows, reporting relationships, or the scalar chain. Usually, the formal organizational structure is presented through an organization chart.

The Traditional Organizational Structure

The traditional organizational structure typically has six types;

- functional structure,

- product structure,

- geographical structure,

- matrix structure,

- customer structure, and

- process structure.

Functional Structure groups employees with similar skills, doing similar tasks, sharing technical expertise and responsibilities, and working within their areas of expertise.

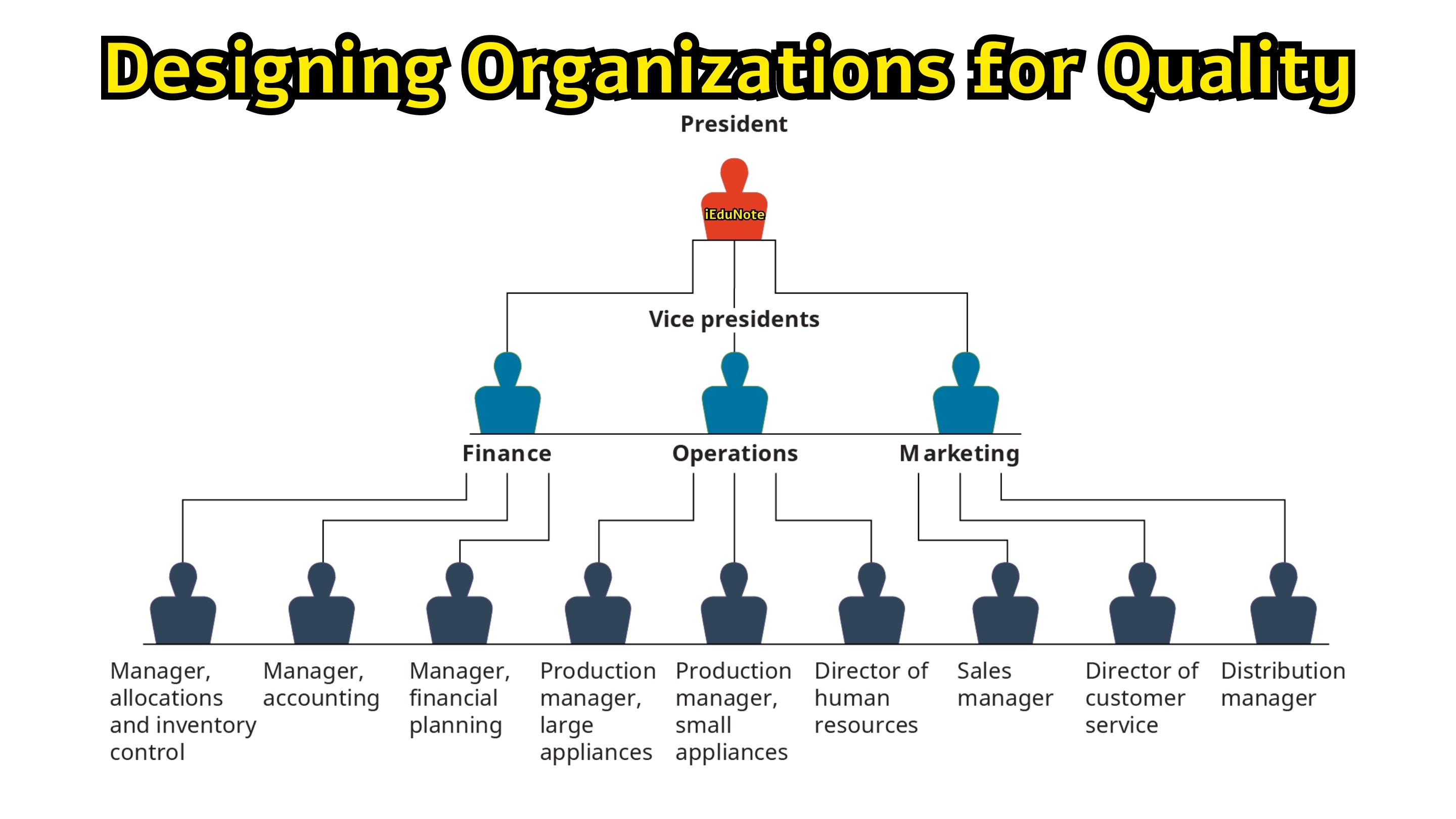

The figure below shows an example of a functional structure. In such organizations, communication occurs vertically up or down the chain of command.

This structure allows people to specialize in the aspects of the work for which they are best suited. They also make it easy to evaluate people based on a narrow but clear set of responsibilities. For these reasons, functional structures are common in manufacturing and service organizations.

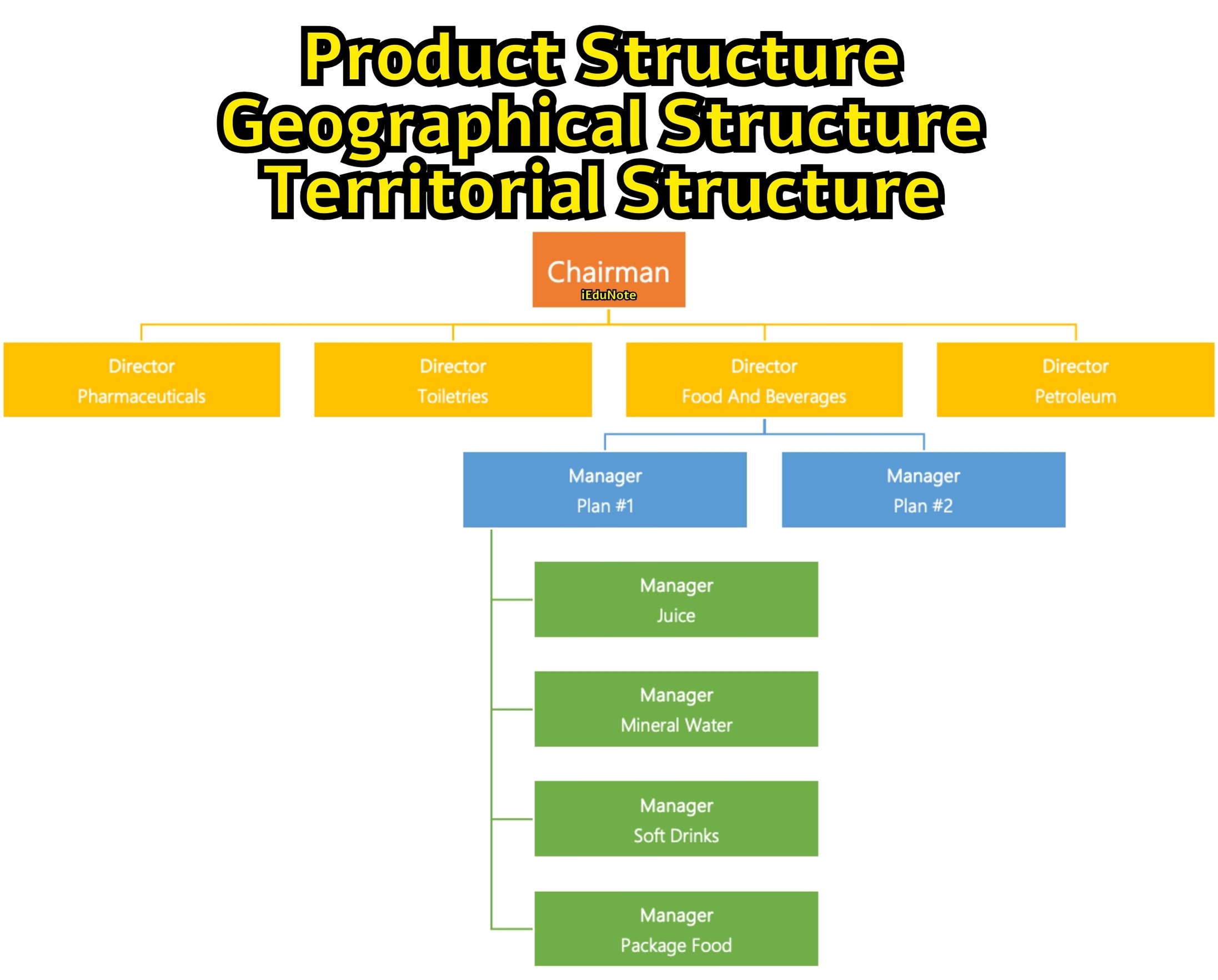

Product Structure groups employees with responsibility regarding the same product or product line. The figure above shows an example of product structure. In such organizations, communication also occurs vertically up or down the chain of command.

This structure allows people to specialize in the work related to a product or product line for which they are best suited. Here, the person responsible for a product or product line also looks after all the functions related to the product or product line.

Here, people are evaluated based on a wide but clear set of responsibilities. For these reasons, product structures are common in manufacturing organizations where various products are produced.

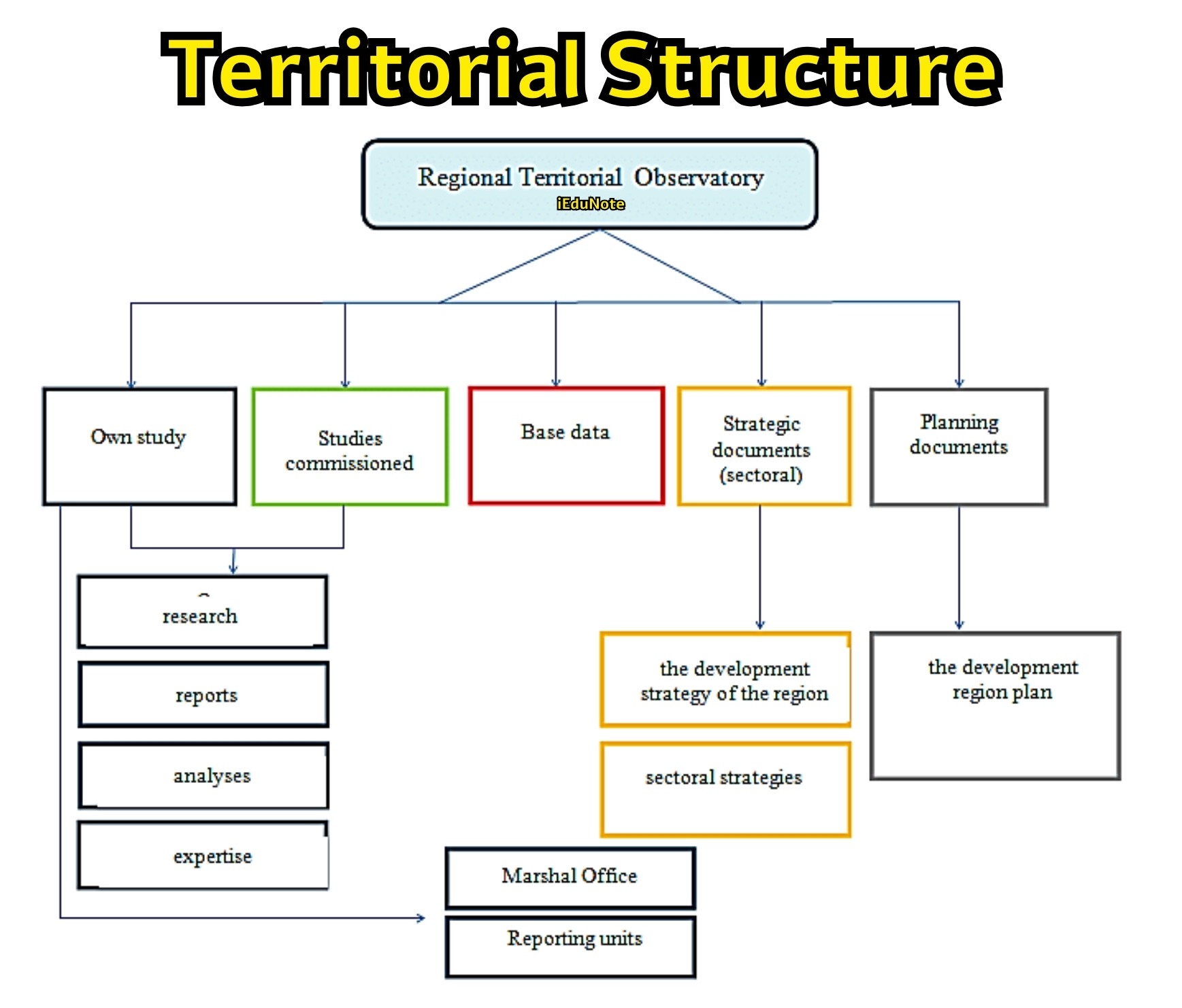

Product, geographical, or territorial structures are based on geographical area. The principle is that all activities in a given area or territory should be grouped and assigned to a manager.

A typical territorial structure is shown in the figure below. This type of structure is beautiful to large-scale firms or other enterprises whose activities are physically or geographically spread.

Territorial structure is proper when its purpose is to encourage local participation in decision-making and to take advantage of certain economies of localized operations.

Problems with the Traditional Organizational Structure

Traditional organizational structure is designed primarily for administrative convenience rather than providing customers with high-quality service. Despite some advantages of traditional organizational structure, there are some disadvantages also.

Today’s world is a highly competitive global market. Every organization tries to compete successfully and be the top scorer in their field.

Practice of the principles of Total Quality Management helps them do so. However, those organizations’ organizational structures are creating problems in success.

For example, TQM requires customer satisfaction. Only by satisfying the customers can the organization survive and improve.

However, the traditional structure keeps the management far beyond the customers. A few employees may be involved with the customer, which is not enough to satisfy customers properly.

Again, teamwork is very important for success.

However, the traditional structure follows a satisfying strategy. Top-level managers are the next-level bosses, and the lower-level managers always try to satisfy the upper-level managers.

Many organizational levels are present here, and every individual tries to satisfy his/her boss, which produces lower productivity. If there is the practice of teamwork, productivity may be increased.

Furthermore, traditional structures practice quality control or quality assurance departments to ensure the quality of the products or services.

However, ensuring quality by checking or assessing the product is not helpful. Functional structure inhibits process improvement. No organizational unit controls a whole process, although most processes involve many functions.

In a word, the traditional organizational structure compromises total quality in several ways. It keeps people away from customers and insulates them from customer expectations.

It promotes complex and wasteful processes and inhibits process improvement. It separates the quality function from the rest of the organization, giving people an excuse for not worrying about quality.

Redesigning Organizations for Quality

One of Deming’s 14 points is to “break down barriers between departments” because “people in various departments must work as a team.”

This point covers what the TQ philosophy entails for organizational design. People cannot contribute to customer satisfaction and continuous improvement if they are confined to functional persons who cannot see the customers or hear their voices.

Organizational actors and processes do not exist in a vacuum but are embedded in a larger organizational system with distinct structural characteristics.

Companies have employed various structural options to deal with the increased complexity, uncertainty, and interdependence accompanying TQM implementation.

Hence, understanding the company’s structure should give us greater insight into the effective implementation of TQM.

Total Quality Management (TQM) is an integrative management concept for continuously improving the quality of goods and services delivered through the participation of all levels and functions of the organization.

It is the process of building quality into goods and services from the beginning and making quality the concern and responsibility of every person in the organization.

As mentioned, few studies have directly addressed the connection between mechanistic/organic structures and TQM outcomes.

Researchers, however, have investigated the connection between TQM and various structure components, such as team-based and participative structures. The following paragraphs discuss our hypothesized connection between organizational structure and TQM effectiveness.

TQM emphasizes empowering employees to make decisions and use their own intelligence. It requires employees to identify and diagnose quality problems and take corrective actions without going through the management hierarchy.

Participation is encouraged by recognizing employee accomplishments and providing continuous feedback.

These aspects of TQM suggest that it is less likely to be effective in companies with mechanistic structures that centralize decision-making authority in managerial hands and use direct, inflexible control mechanisms.

In organic structures, however, employees are given the latitude to make appropriate decisions within system parameters.

Several studies suggest that a participative structure can improve TQM outcomes.

Hence, organizations with flexibility-oriented organic structures characterized by such employee involvement, empowerment, and responsibility for quality at the source appear to show a better fit with TQM practices.

TQM also requires a move away from vertical lines of communication and toward communication across departments, organizational levels, functions, product lines, and locations.

These open and informal lines of communication can help solve problems and enable more rapid implementation of change. Horizontal coordination is encouraged based on the flow of work processes across functional areas through mechanisms such as cross-functional teams.

These characteristics of TQM are unlikely to find a match in mechanistic structures that emphasize hierarchical chains of command.

In contrast, organic structures stress coordination through horizontal communication networks and horizontal job dependency. Several studies suggest that team-based structure (a component of organic structure) improves TQM effectiveness.

Hence, companies with flexibility-oriented organic structures with horizontal coordination and communication networks are more likely to effectively implement TQM.

The TQM philosophy of obtaining customer feedback, meeting and exceeding the needs of external as well as internal customers, and blurring boundaries between the organization, suppliers, and customers are likely to be less effective in organizations with mechanistic structures because they have more internal focus and tend to pay less attention to the company’s interdependence with the environment.

The TQM philosophy appears to be a better match in companies with organic structures that focus on the external factors influencing the company.

Similarly, the TQM concept of benchmarking industry best practices is more likely to be effective in companies with flexibility-oriented organic structures that consider themselves interdependent with other entities in the environment.

Organizations with mechanistic structures focus on predictability, which, in turn, increases control. However, when the environment is dynamic, inflexible control structures can prevent the organization from reacting quickly and changing.

Companies with organic structures tend to be more open to change and match with the TQM emphasis on change and learning through strategies such as benchmarking, employee training, cross-functional teams, and experimentation.

The “kaizen” philosophy of small and continuous improvements is, thereby, more likely to be effective in companies with flexibility-oriented organic structures that operate under the assumption that learning and adapting to change are essential for survival.

The concept of control under TQM also matches with the notion of control under organic structures. Continuous improvement under TQM requires less direct and hierarchical control (as experienced under mechanistic structures) and greater indirect control (as experienced under organic structures).

Hence, under organic structures and under the TQM philosophy, control shifts from vertical hierarchies to horizontal process flows and exists in definitions of quality, performance measures, core quality values, and system parameters.

The preceding discussion suggests that the TQM aspects of responsibility for quality at the source, teamwork, horizontal coordination, focus on the customer, and continuous improvement are more conducive to organic structures than to mechanistic structures.

Hence, companies with organic structures are more likely to experience positive outcomes associated with TQM programs (e.g., reduced service calls, reduced scrap, reduced labor costs, increased productivity, and increased customer satisfaction) compared to those with mechanistic structures.

Organizational structure is one factor that significantly influences TQM effectiveness.

Organizations with flexibility-oriented, organic structures are likely to have higher levels of TQM effectiveness than those with mechanistic structures.

The requirements of the TQM approach–teamwork and coordination, responsibility for quality at the source, focus on customer, and continuous improvement–are more likely to be satisfied in organic companies. To implement TQM successfully, the organizational structure should be as follows.

Internal Customer Structure

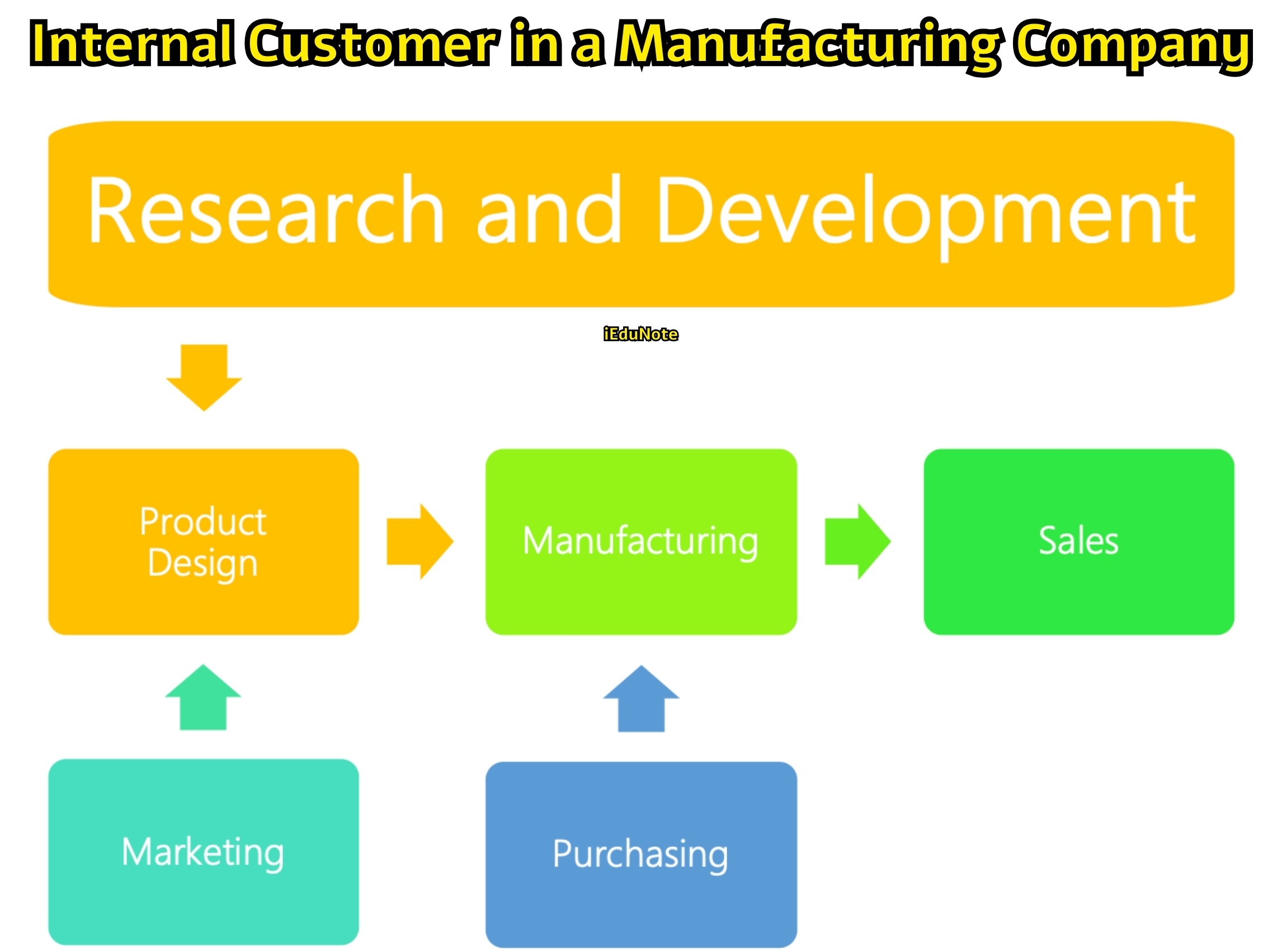

One way an organization can promote quality and teamwork is to recognize the existence of ‘Internal customers’ and to satisfy them. An internal customer is another person, group, or department within the organization who depends on one’s work to get their work done.

In Figure 7.4, Product Design is the internal customer of both the Research and Development and Marketing function; Manufacturing is the internal customer of both Product Design and Purchasing, and Sales is the internal customer of the manufacturing function.

If an organization can concentrate on satisfying internal customers, that can ensure the proper implementation of TQM.

Promoting the idea of internal customers does not change the organization’s structure so much as it changes the way people think about the structure.

Rather than focusing on satisfying their immediate supervisor (vertical), people tend to think about satisfying the next person in the process (horizontal), who is one step closer to the ultimate customer. Satisfying internal customers first is the best way to satisfy external customers.

Team-based Organization

A more substantial organizational redesign involves structuring the organization around teams, each responsible for carrying out and improving one of the organization’s core processes.

Depending on the size and the nature of the organization and the processes, the teams may include everyone contributing to a given process or only a representative subset. The teams may meet

continuously until their new process design is complete, after which they may meet periodically or on an ad hoc basis whenever necessary.

This approach eliminates many of the problems with the traditional structure. If a team has responsibility for an entire process, they don’t have to worry that their improvement efforts will be undetermined-intentionally or unintentionally- by the actions of another group.

Substantial organizational improvement can be created using processes as a grouping method. Here, people are allowed to see and change procedures they couldn’t see or change in the traditional functional structure.

Robert Brookhouse, a member of a process organization at Xerox, puts it, “When you create a flow [Xerox term for process organization], you find where you’re wasting time, doing things twice. And because we own the entire process, we can change it.”

This does not suggest that changing to a process-based organization is simple and easy. Rather, it takes a lot of thought because it means essentially taking the organization apart and putting it back together again.

As Robert Knorr and Edward Thiede describe it:

The restructuring should begin by defining each process’s operations, information, and skill needs.

Process definition also answers key questions about the lines of integration needed among processes and functions, such as who must be interested and when.

What changes are needed in upstream processes to accommodate the needs of those downstream, and vice versa?

Mark Kelly provides an example of an organizational structure based on teams in The Adventures of a Self-Managing Team.

The building blocks of the “Clear Lake Plant” organization are process based teams. Tasks that transcend processes (such as innovation and safety) are handled in task teams made up of members drawn from each process team. The team-based organizational structure is depicted in Figure 7.5:

Reduce Hierarchy

A third type of structural change that often results from a focus on internal customers and the creation of process teams is a reduction in the number of hierarchical layers in the organization.

Several levels of middle management are eliminated in this system. This reduction in middle management is also facilitated by advances in information systems that have taken over many of the information summarization and transmission roles formerly played by middle managers.

With the elimination of non-value-added activities and the empowerment of front-line workers to improve processes, there is also less supervision and coordination for managers.

An additional benefit of such “flatter” organizations is improved communication between top managers and front-line employees. This is not to say that this type of structure has any drawbacks.

The main drawback is that sometimes many people- lose their jobs. This is a significant disruption in the lives of the affected individuals and a loss of their experience in the organization.

Furthermore, the employees’ morale in the organization may suffer. For all of these reasons, organizations should approach flattening with an attitude of caution and concern.

Creation Steering Committees

A fourth type of structural change associated with TQ is creating a high-level planning group entrusted with the responsibility of guiding the organization’s quality efforts.

Such groups- called steering committees, quality councils, or quality improvement teams- are a key part of many firms’ quality improvement efforts and an important part of the quality recommendations of both Juran and Crosby.

Such groups provide a means of demonstrating and increasing the organization’s commitment to quality, as well as a mechanism for coordinating the efforts of various organizational units.

Although many firms use only top managers in such groups, Portman Equipment Company- an industrial equipment sales, service, and rental company- uses people from all types of jobs.

Organizational Design for Quality in Action

Promoting the concept of internal customers, forming process teams, reducing hierarchy, and creating steering committees all facilitate quality. This section presents examples of organizations that use these ideas to ensure or improve quality in their operations.

Kaizen

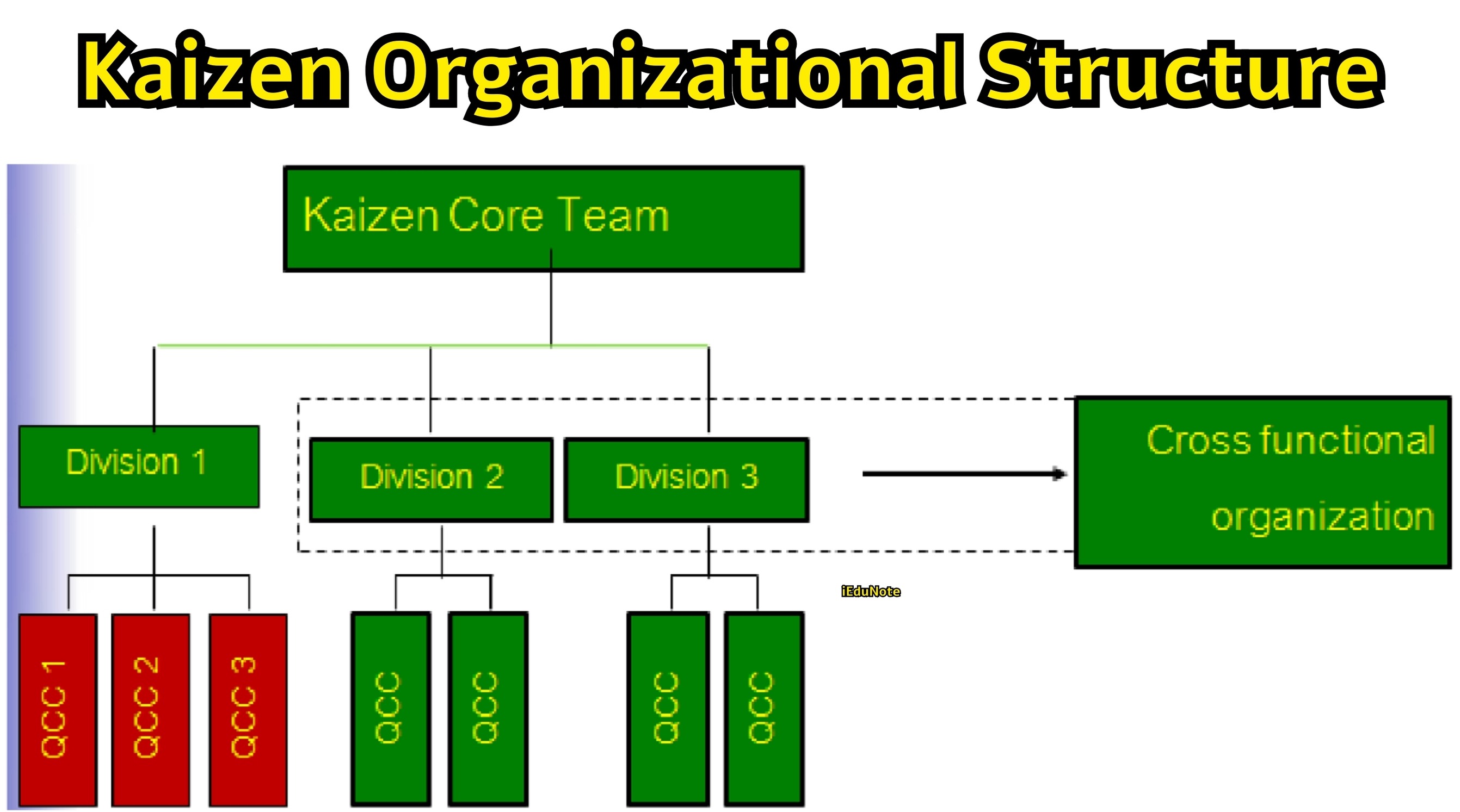

Far to the east, many Japanese companies are organized in accordance with kaizen, the philosophy of continuous improvement.

Underlying Kaizen is the belief that a great number of small improvements over time will create substantial improvement in organizational performance.

Although Japanese organizations practicing Kaizen often maintain their functional structure, they superimpose on it a cross-functional management structure charged with continuous improvement of quality, cost, and ability to meet schedules (Figure 7.6); each year, top management articulates goals for improvements of cross-functional activities, which the kaizen management structure is designed to attain. Such efforts have been broadened in some Japanese organizations to include employee morale.

Shigeru Aoki, senior managing director at Toyota, explains the relationships among competitive success and cross-functional goals such as quality and line organization.

The ultimate goal of a company is to make profits.

Assuming this is self-evident, then the company’s next “superordinate” goals should be such cross-functional goals as quality, cost, and scheduling (quantity and delivery).

Without achieving these goals, the company will be left behind by the competition because of interior quality, will find its profits eroded by higher costs, and will be unable to deliver the products in time for customers. If these cross-functional goals are realized, profits will follow.

Therefore, we should consider all the other management functions existing to serve the three superordinate goals.

These auxiliary management functions include product planning, design, production, purchasing, and marketing, and they should be regarded as secondary means to achieve QCS (quality, cost, and scheduling)

Islamic Perspectives on Structure

In ancient civilizations and societies before the Industrial Revolution, various forms of organizations existed, and some operated across cultures and continents. The structures of those organizations were not as formal and not as well articulated as those of today’s corporations.

Indeed, the formal organizational structure is an innovative form characteristically linked to and associated with the emergence of large Western business organizations in the second half of the 1800s.

Since these corporations are the creations of human beings, they are always subject to human decisions.

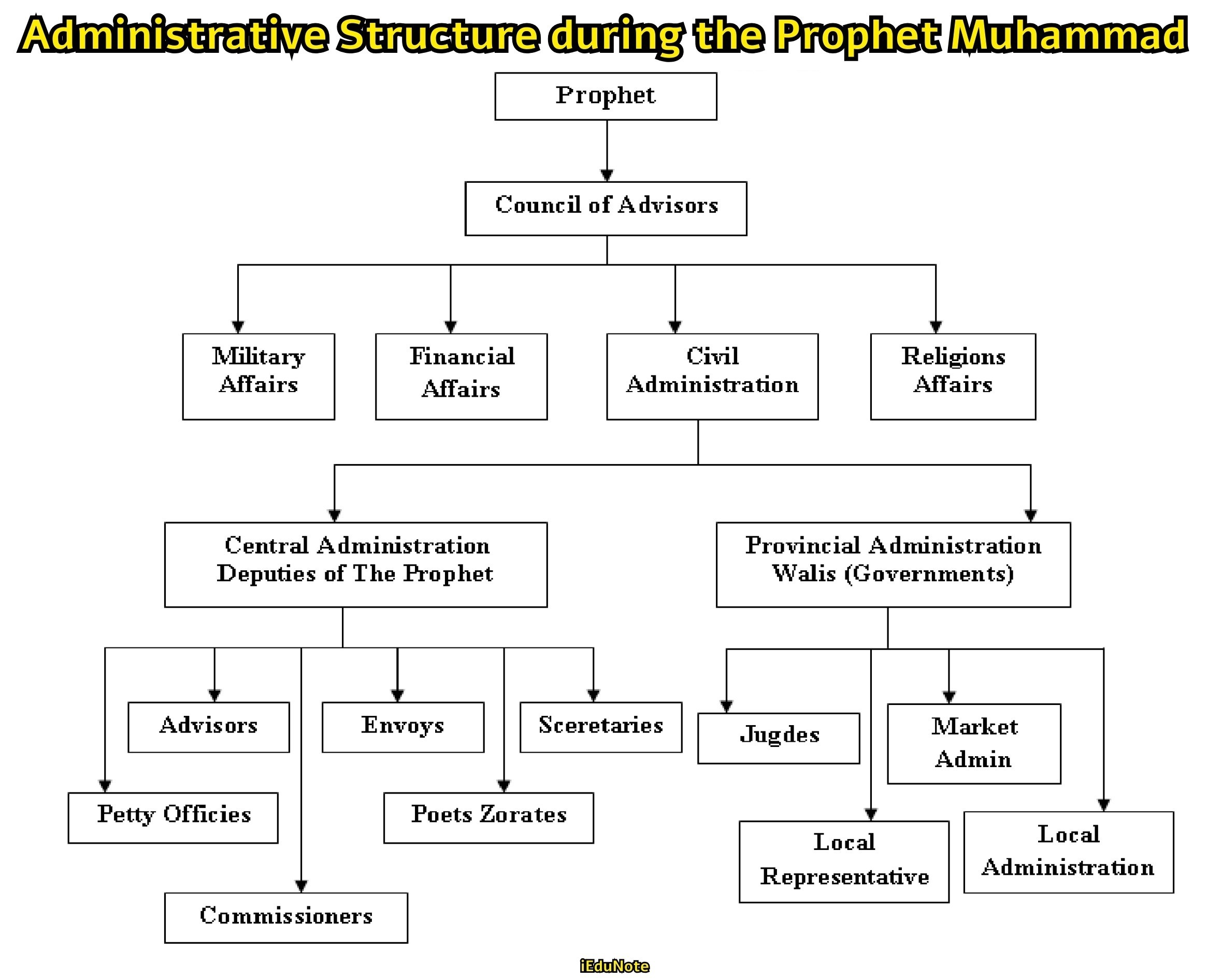

During the early years of Islam and the start of the Islamic state, the Prophet Muhammad (SAW) gradually organized state and economic affairs.

The state organization was simple. There were the military, civil administration, financial and religious affairs, and almost uniformly, a unit responsible for surveillance.

The latter, however, appeared to be informal, and its members were frequently changed according to the pressing situation.

Civil administration affairs were divided into two departments: central administration (deputies, advisors, secretaries, envoys, commissioners, poets and orators, petty officials) and provincial administration (governors, local administrators, and local representatives, judges, and market administrators) (See Figure 7.7).

Administrators and officers were given autonomy to run their duties. Though the structure appeared hierarchical, it was loose as all the officers, regardless of their level in the organization, had the right to approach the Prophet (SAW) or his deputies and report their problems.

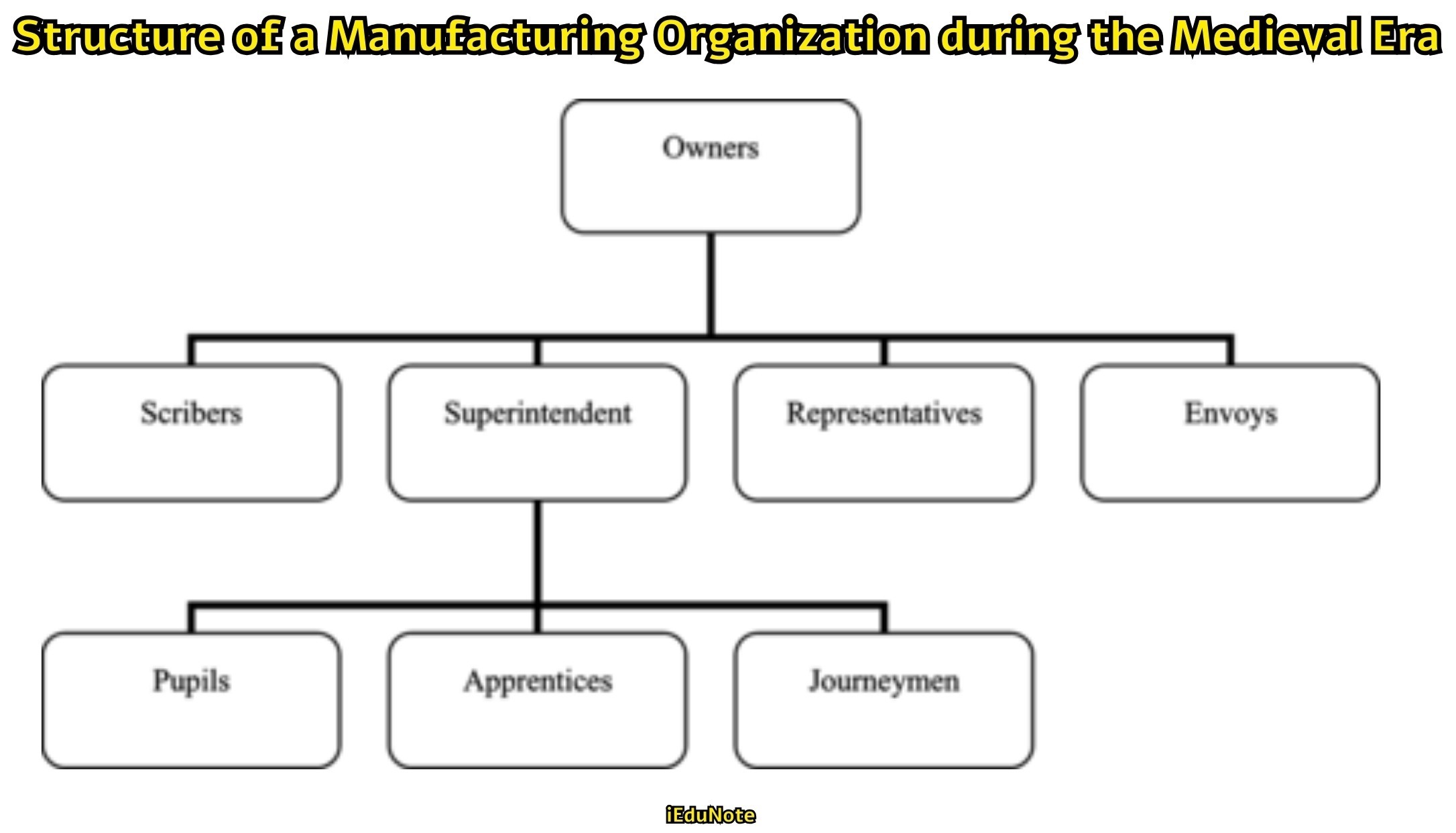

As per recorded history, industry and tradehouses were common in the Islamic world during Medieval times. The businesses were either family-owned or partnerships. In either case, the owner-manager performed the work with the help of subordinates or directly supervising subordinates.

Subordinates were classified into two categories: scribers (responsible for correspondence and recording transactions) and those who carried out the core work. Those include both the Ista (senior craftsman or superintendent) and workers.

The latter were classified into three categories: tilmidh (pupil), ghulam (apprentice), and ajir (journeyman).

The pupil could provide some help but mostly learned through observation. The apprentice assumed part of the work under direct supervision. The journeyman was a permanent worker or craftsman.

Depending on the size of the business, there might be business representatives and envoys in other cities. The envoys could be any people working in the business or a designated person within the organization.

The figure below depicts the organizational structure of a company during that era. It should be stated again that the lines depict only those in authority as relationships and lines of communication were open, two-way, and lacked formality.

Comparison of Theories of Organizational Design

This section compares the total quality view of organizational design with the viewpoint from organization theory. Topics discussed are structural contingency theory and the institutional theory of organization structure.

Structural Contingency Theory

The structural contingency model originated in the 1960s and is the dominant view of organizational design in the management literature.

According to this view, the two principal types of organization structures are mechanistic (centralized, many rules, strict division of labor, formal coordination across departments) and organic (decentralized, few rules, loose division of labor, informal coordination across departments).

These structures are described in detail in most management and organizational theory textbooks.

The structural contingency model holds that there is no “one best way” to organize and that the choice between mechanistic and organic structures should be a function of certain contingencies, most often characteristics of the organization’s environment and technology.

The choice between mechanistic and organic structures is usually seen as a function of uncertainty. Organizations face great uncertainty if their environments are complex and changing and if the technology they use in creating their products is not well understood.

The microcomputer industry is a good example of this type of industry. The contingency model says that organizations facing uncertainty should adopt an organic structure.

On the other hand, organizations that experience little uncertainty- their environments are simple and stable, and their technology is well understood need a mechanistic structure.

The rationale for these recommendations is that organic organizations can better process the information necessary to deal with a complex environment and uncertain technology. They are also more flexible and can adapt to the changing circumstances associated with an unstable environment.

However, this information processing and adaptive capacity comes at the expense of efficiency and control.

Although mechanistic organizations may be unable to accomplish uncertain tasks or change rapidly, they are better suited for accomplishing straightforward tasks in a predictable environment.

The mechanistic organization will accomplish such tasks quite reliably, with little danger of employees engaging in costly experiments to see if there is a better way to do the job. The organic organization sacrifices reliability for flexibility.

A quality-oriented organization practicing continuous improvement cannot afford to freeze its processes by using a mechanistic structure.

Most organizations practicing total quality move in the direction of organic structures. The number of levels in their hierarchy decreases, teams are created, and employees are given the authority and the responsibility to develop new and better ways of accomplishing their tasks.

Coordination also tends toward the informal, as interdependent people can coordinate their work on a personal basis without the interference of a bureaucratic hierarchy.

The relatively broader jobs in a TQ company give employees a better sense of how their work contributes to customer satisfaction, whether customers are internal or external.

How can the “one best way” approach of the quality movement be justified in light of organization theory’s historical endorsement of a contingency approach to design?

It may be that few industries and technologies are simple and stable enough for a mechanistic design to operate effectively. A second possibility is that TQ designs have capacities for producing efficiencies unanticipated in the old mechanistic-organic distinction.

Once the improvement of a particular process has reached the point where it is impractical to search for further gains, teams may establish the process as their standard and attempt to recreate it perfectly each time without the involvement of their managers.

In other words, efficiencies would be treated through methods different from those used in mechanistic firms.

A third possibility is that TQ-oriented firms pay a price in efficiency for their organizational structures but that the superior quality of their products more than makes up for the higher prices that a lack of efficiency entails.

Such firms would be unlikely to compete in markets such as textiles, where the price is the overriding competitive factor.

A final possibility is that firms structured to achieve quality are paying a price for efficiency that is not offset by their advantages. In this case, such structures are not viable in the long run. This possibility is not the case, based on the limited available information.

Institutional Theory

Structural contingency theory, like most organizational design theories, assumes that organizations choose structures to help them perform better, provide high quality, have low costs, etc.

On the other hand, institutional theory holds that organizations try to succeed by creating structures that will be seen as appropriate by important external constituencies- customers, other organizations in the industry, government agencies, etc.

According to institutional theory, an aspect of organizational structure need not contribute to organizational performance to be worthwhile.

Adopting a certain structure helps the organization be seen as legitimate in the eyes of those who have the power to determine the organization’s fate, and then it is worthwhile.

For example, many businesses have departments devoted to achieving environmental goals.

From an institutional theory standpoint, it is important to ask whether quality-oriented organization designs that include steering committees and extensive use of teams are intended to promote quality or merely legitimize the organization as a progressive, quality-conscious organization.

In some settings, the adoption of quality-oriented structures is motivated primarily by institutional concerns.

For example, any company that wishes to compete in Europe must be certified to comply with the ISO-9000 quality standards.

Thus, institutional theory provides another way of thinking about the rapid explosion of quality-oriented structures in organizations.

Although some organizations may primarily seek higher performance by adopting teams and steering committees, others may primarily seek the approval of important constituencies.

Conclusion

Problems with traditional organizational structure have led many quality-oriented organizations to abandon this structure. New structures feature internal customers, process teams, less hierarchy, and quality steering committees.

Although the widespread use of quality-oriented organic structures may be inconsistent with structural contingency theory, more companies are restructuring their organizations for quality. Some companies adopt quality-oriented structures to appear legitimate in the eyes of important groups in their industry.